Understanding zip() Function

The zip() function in Python is a built-in function that provides an efficient way to iterate over multiple lists simultaneously. As this is a built-in function, you don’t need to import any external libraries to use it.

The zip() function takes two or more iterable objects, such as lists or tuples, and combines each element from the input iterables into a tuple. These tuples are then aggregated into an iterator, which can be looped over to access the individual tuples.

Here is a simple example of how the zip() function can be used:

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c'] zipped = zip(list1, list2) for item1, item2 in zipped: print(item1, item2)

Output:

1 a 2 b 3 c

The function also works with more than two input iterables:

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c'] list3 = [10, 20, 30] zipped = zip(list1, list2, list3) for item1, item2, item3 in zipped: print(item1, item2, item3)

Output:

1 a 10 2 b 20 3 c 30

Keep in mind that the zip() function operates on the shortest input iterable. If any of the input iterables are shorter than the others, the extra elements will be ignored. This behavior ensures that all created tuples have the same length as the number of input iterables.

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b'] zipped = zip(list1, list2) for item1, item2 in zipped: print(item1, item2)

Output:

1 a 2 b

To store the result of the zip() function in a list or other data structure, you can convert the returned iterator using functions like list(), tuple(), or dict().

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c'] zipped = zip(list1, list2) zipped_list = list(zipped) print(zipped_list)

Output:

[(1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), (3, 'c')]

Feel free to improve your Python skills by watching my explainer video on the zip() function:

Working with Multiple Lists

Working with multiple lists in Python can be simplified by using the zip() function. This built-in function enables you to iterate over several lists simultaneously, while pairing their corresponding elements as tuples.

For instance, imagine you have two lists of the same length:

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c']

You can combine these lists using zip() like this:

combined = zip(list1, list2)

The combined variable would now contain the following tuples: (1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), and (3, 'c').

To work with multiple lists effectively, it’s essential to understand how to get specific elements from a list. This knowledge allows you to extract the required data from each list element and perform calculations or transformations as needed.

In some cases, you might need to find an element in a list. Python offers built-in list methods, such as index(), to help you search for elements and return their indexes. This method is particularly useful when you need to locate a specific value and process the corresponding elements from other lists.

As you work with multiple lists, you may also need to extract elements from Python lists based on their index, value, or condition. Utilizing various techniques for this purpose, such as list comprehensions or slices, can be extremely beneficial in managing and processing your data effectively.

multipled = [a * b for a, b in zip(list1, list2)]

The above example demonstrates a list comprehension that multiplies corresponding elements from list1 and list2 and stores the results in a new list, multipled.

In summary, the zip() function proves to be a powerful tool for combining and working with multiple lists in Python. It facilitates easy iteration over several lists, offering versatile options to process and manipulate data based on specific requirements.

Creating Tuples

The zip() function in Python allows you to create tuples by combining elements from multiple lists. This built-in function can be quite useful when working with parallel lists that share a common relationship. When using zip(), the resulting iterator contains tuples with elements from the input lists.

To demonstrate once again, consider the following two lists:

names = ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"] ages = [25, 30, 35]

By using zip(), you can create a list of tuples that pair each name with its corresponding age like this:

combined = zip(names, ages)

The combined variable now contains an iterator, and to display the list of tuples, you can use the list() function:

print(list(combined))

The output would be:

[('Alice', 25), ('Bob', 30), ('Charlie', 35)]

Zip More Than Two Lists

The zip() function can also work with more than two lists. For example, if you have three lists and want to create tuples that contain elements from all of them, simply pass all the lists as arguments to zip():

names = ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"] ages = [25, 30, 35] scores = [89, 76, 95] combined = zip(names, ages, scores) print(list(combined))

The resulting output would be a list of tuples, each containing elements from the three input lists:

[('Alice', 25, 89), ('Bob', 30, 76), ('Charlie', 35, 95)]

Note: When dealing with an uneven number of elements in the input lists,

Note: When dealing with an uneven number of elements in the input lists, zip() will truncate the resulting tuples to match the length of the shortest list. This ensures that no elements are left unmatched.

Use zip() when you need to create tuples from multiple lists, as it is a powerful and efficient tool for handling parallel iteration in Python.

Working with Iterables

A useful function for handling multiple iterables is zip(). This built-in function creates an iterator that aggregates elements from two or more iterables, allowing you to work with several iterables simultaneously.

Using zip(), you can map similar indices of multiple containers, such as lists and tuples. For example, consider the following lists:

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c']

You can use the zip() function to combine their elements into pairs, like this:

zipped = zip(list1, list2)

The zipped variable will now contain an iterator with the following element pairs: (1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), and (3, 'c').

It is also possible to work with an unknown number of iterables using the unpacking operator (*).

Suppose you have a list of iterables:

iterables = [[1, 2, 3], "abc", [True, False, None]]

You can use zip() along with the unpacking operator to combine their corresponding elements:

zipped = zip(*iterables)

The result will be: (1, 'a', True), (2, 'b', False), and (3, 'c', None).

Note: If you need to filter a list based on specific conditions, there are other useful tools like the

Note: If you need to filter a list based on specific conditions, there are other useful tools like the filter() function. Using filter() in combination with iterable handling techniques can optimize your code, making it more efficient and readable.

Using For Loops

The zip() function in Python enables you to iterate through multiple lists simultaneously. In combination with a for loop, it offers a powerful tool for handling elements from multiple lists. To understand how this works, let’s delve into some examples.

Suppose you have two lists, letters and numbers, and you want to loop through both of them. You can employ a for loop with two variables:

letters = ['a', 'b', 'c'] numbers = [1, 2, 3] for letter, number in zip(letters, numbers): print(letter, number)

This code will output:

a 1 b 2 c 3

Notice how zip() combines the elements of each list into tuples, which are then iterated over by the for loop. The loop variables letter and number capture the respective elements from both lists at once, making it easier to process them.

If you have more than two lists, you can also employ the same approach. Let’s say you want to loop through three lists, letters, numbers, and symbols:

letters = ['a', 'b', 'c'] numbers = [1, 2, 3] symbols = ['@', '#', '$'] for letter, number, symbol in zip(letters, numbers, symbols): print(letter, number, symbol)

The output will be:

a 1 @ b 2 # c 3 $

Unzipping Elements

In this section, we will discuss how the zip() function works and see examples of how to use it for unpacking elements from lists. For example, if you have two lists list1 and list2, you can use zip() to combine their elements:

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c'] zipped = zip(list1, list2)

The result of this operation, zipped, is an iterable containing tuples of elements from list1 and list2. To see the output, you can convert it to a list:

zipped_list = list(zipped) # [(1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), (3, 'c')]

Now, let’s talk about unpacking elements using the zip() function. Unpacking is the process of dividing a collection of elements into individual variables. In Python, you can use the asterisk * operator to unpack elements. If we have a zipped list of tuples, we can use the * operator together with the zip() function to separate the original lists:

unzipped = zip(*zipped_list) list1_unpacked, list2_unpacked = list(unzipped)

In this example, unzipped will be an iterable containing the original lists, which can be converted back to individual lists using the list() function:

list1_result = list(list1_unpacked) # [1, 2, 3] list2_result = list(list2_unpacked) # ['a', 'b', 'c']

The above code demonstrates the power and flexibility of the zip() function when it comes to combining and unpacking elements from multiple lists. Remember, you can also use zip() with more than two lists, just ensure that you unpack the same number of lists during the unzipping process.

Working with Dictionaries

Python’s zip() function is a fantastic tool for working with dictionaries, as it allows you to combine elements from multiple lists to create key-value pairs. For instance, if you have two lists that represent keys and values, you can use the zip() function to create a dictionary with matching key-value pairs.

keys = ['a', 'b', 'c'] values = [1, 2, 3] new_dict = dict(zip(keys, values))

The new_dict object would now be {'a': 1, 'b': 2, 'c': 3}. This method is particularly useful when you need to convert CSV to Dictionary in Python, as it can read data from a CSV file and map column headers to row values.

Sometimes, you may encounter situations where you need to add multiple values to a key in a Python dictionary. In such cases, you can combine the zip() function with a nested list comprehension or use a default dictionary to store the values.

keys = ['a', 'b', 'c']

values1 = [1, 2, 3]

values2 = [4, 5, 6] nested_dict = {key: [value1, value2] for key, value1, value2 in zip(keys, values1, values2)}

Now, the nested_dict object would be {'a': [1, 4], 'b': [2, 5], 'c': [3, 6]}.

Itertools.zip_longest()

When you have uneven lists and still want to zip them together without missing any elements, then itertools.zip_longest() comes into play. It provides a similar functionality to zip(), but fills in the gaps with a specified value for the shorter iterable.

from itertools import zip_longest list1 = [1, 2, 3, 4] list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c'] zipped = list(zip_longest(list1, list2, fillvalue=None)) print(zipped)

Output:

[(1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), (3, 'c'), (4, None)]

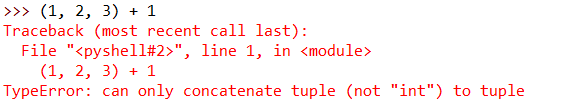

Error Handling and Empty Iterators

When using the zip() function in Python, it’s important to handle errors correctly and account for empty iterators. Python provides extensive support for exceptions and exception handling, including cases like IndexError, ValueError, and TypeError.

An empty iterator might arise when one or more of the input iterables provided to zip() are empty. To check for empty iterators, you can use the all() function and check if iterables have at least one element. For example:

def zip_with_error_handling(*iterables): if not all(len(iterable) > 0 for iterable in iterables): raise ValueError("One or more input iterables are empty") return zip(*iterables)

To handle exceptions when using zip(), you can use a try–except block. This approach allows you to catch and print exception messages for debugging purposes while preventing your program from crashing. Here’s an example:

try: zipped_data = zip_with_error_handling(list1, list2) except ValueError as e: print(e)

In this example, the function zip_with_error_handling() checks if any of the input iterables provided are empty. If they are, a ValueError is raised with a descriptive error message. The try–except block then catches this error and prints the message without causing the program to terminate.

By handling errors and accounting for empty iterators, you can ensure that your program runs smoothly when using the zip() function to get elements from multiple lists. Remember to use the proper exception handling techniques and always check for empty input iterables to minimize errors and maximize the efficiency of your Python code.

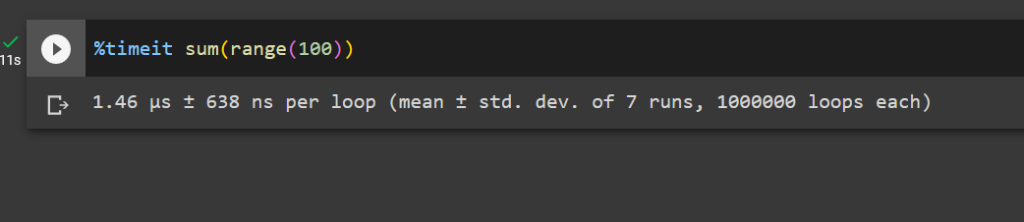

Using Range() with Zip()

Using the range() function in combination with the zip() function can be a powerful technique for iterating over multiple lists and their indices in Python. This allows you to access the elements of multiple lists simultaneously while also keeping track of their positions in the lists.

One way to use range(len()) with zip() is to create a nested loop. First, create a loop that iterates over the range of the length of one of the lists, and then inside that loop, use zip() to retrieve the corresponding elements from the other lists.

For example, let’s assume you have three lists containing different attributes of products, such as names, prices, and quantities.

names = ["apple", "banana", "orange"] prices = [1.99, 0.99, 1.49] quantities = [10, 15, 20]

To iterate over these lists and their indices using range(len()) and zip(), you can write the following code:

for i in range(len(names)): for name, price, quantity in zip(names, prices, quantities): print(f"Index: {i}, Name: {name}, Price: {price}, Quantity: {quantity}")

This code will output the index, name, price, and quantity for each product in the lists. The range(len()) construct generates a range object that corresponds to the indices of the list, allowing you to access the current index in the loop.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to use zip with a for loop in Python?

Using zip with a for loop allows you to iterate through multiple lists simultaneously. Here’s an example:

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c'] for num, letter in zip(list1, list2): print(num, letter) # Output: # 1 a # 2 b # 3 c

Can you zip lists of different lengths in Python?

Yes, but zip will truncate the output to the length of the shortest list. Consider this example:

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b'] for num, letter in zip(list1, list2): print(num, letter) # Output: # 1 a # 2 b

What is the process to zip three lists into a dictionary?

To create a dictionary from three lists using zip, follow these steps:

keys = ['a', 'b', 'c']

values1 = [1, 2, 3]

values2 = [4, 5, 6] zipped = dict(zip(keys, zip(values1, values2)))

print(zipped) # Output:

# {'a': (1, 4), 'b': (2, 5), 'c': (3, 6)}

Is there a way to zip multiple lists in Python?

Yes, you can use the zip function to handle multiple lists. Simply provide multiple lists as arguments:

list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c'] list3 = [4, 5, 6] for num, letter, value in zip(list1, list2, list3): print(num, letter, value) # Output: # 1 a 4 # 2 b 5 # 3 c 6

How to handle uneven lists when using zip?

If you want to keep all elements from the longest list, you can use itertools.zip_longest:

from itertools import zip_longest list1 = [1, 2, 3] list2 = ['a', 'b'] for num, letter in zip_longest(list1, list2, fillvalue=None): print(num, letter) # Output: # 1 a # 2 b # 3 None

Where can I find the zip function in Python’s documentation?

The zip function is part of Python’s built-in functions, and its official documentation can be found on the Python website.

Recommended: 26 Freelance Developer Tips to Double, Triple, Even Quadruple Your Income

Recommended: 26 Freelance Developer Tips to Double, Triple, Even Quadruple Your Income

The post Python zip(): Get Elements from Multiple Lists appeared first on Be on the Right Side of Change.

Story: Alice has just been orange-pilled and decides to spend a few hours reading Bitcoin articles.

Story: Alice has just been orange-pilled and decides to spend a few hours reading Bitcoin articles.

Renewable energy often provides a more cost-effective solution, leading miners to gravitate towards these sources naturally:

Renewable energy often provides a more cost-effective solution, leading miners to gravitate towards these sources naturally:

The Bitcoin Mining Council (BMC), a global forum of mining companies that represents 48.4% of the worldwide bitcoin mining network, estimated that in Q4 2022, renewable energy sources accounted for 58.9% of the electricity used to mine bitcoin, a significant improvement compared to 36.8% estimated in Q1 2021 (

The Bitcoin Mining Council (BMC), a global forum of mining companies that represents 48.4% of the worldwide bitcoin mining network, estimated that in Q4 2022, renewable energy sources accounted for 58.9% of the electricity used to mine bitcoin, a significant improvement compared to 36.8% estimated in Q1 2021 (

Bitcoin’s energy consumption is not merely a drain on resources but a strategic tool for enhancing the energy system’s efficiency and sustainability.

Bitcoin’s energy consumption is not merely a drain on resources but a strategic tool for enhancing the energy system’s efficiency and sustainability.

In a Nutshell:

In a Nutshell:

To summarize, Bitcoin has the potential to gradually shift our inflationary, high-consumption economy to a deflationary rational consumption economy while providing a more efficient and greener digital financial system that doesn’t rely on centralized parties and has built-in trust and robustness unmatched by any other financial institution.

To summarize, Bitcoin has the potential to gradually shift our inflationary, high-consumption economy to a deflationary rational consumption economy while providing a more efficient and greener digital financial system that doesn’t rely on centralized parties and has built-in trust and robustness unmatched by any other financial institution.

Recommended:

Recommended:

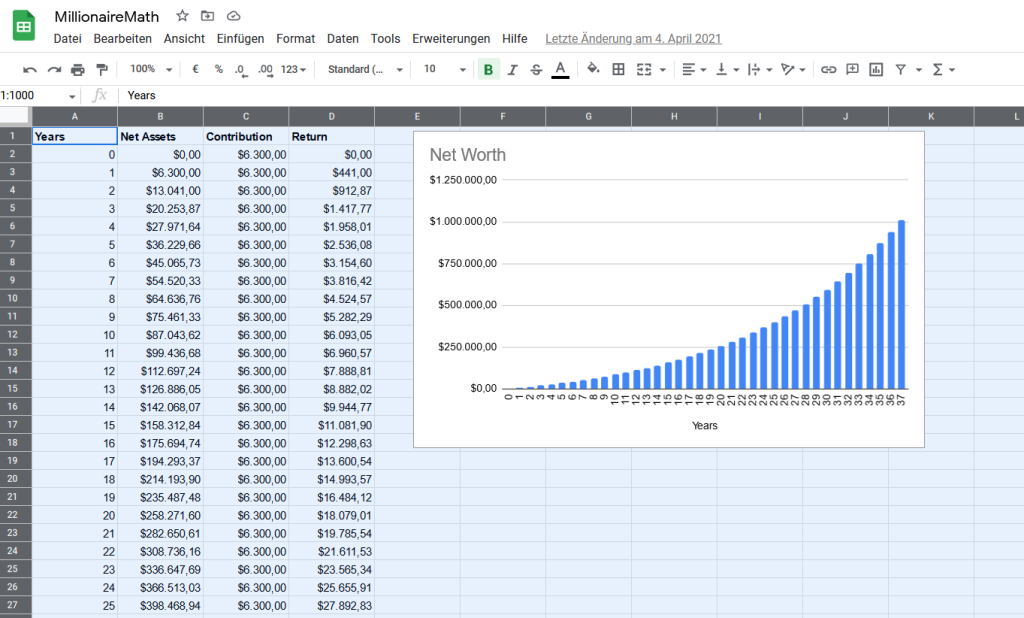

About Me: My investments and business portfolio is worth north of one million USD at the time of writing. While I’m technically financially free in that I don’t have to work anymore to maintain my lifestyle, I love business and finances, so I keep writing blogs for Finxter.

About Me: My investments and business portfolio is worth north of one million USD at the time of writing. While I’m technically financially free in that I don’t have to work anymore to maintain my lifestyle, I love business and finances, so I keep writing blogs for Finxter.

Academy:

Academy:

If your answer is YES!, consider becoming a

If your answer is YES!, consider becoming a

The

The