This tutorial shows you everything you need to know to help you master the essential reverse() method of the most fundamental container data type in the Python programming language.

Definition and Usage:

The list.reverse() reverses the order of the elements in the list. If you want to create a new list with reversed elements, use slicing with negative step size list[::-1].

Here’s a short example:

>>> lst = [1, 2, 3, 4] >>> lst.reverse() >>> lst [4, 3, 2, 1]

In the first line of the example, you create the list lst. You then reverse the order of the elements in the list and print it to the shell.

Code Puzzle — Try It Yourself:

Now you know the basics. Let’s deepen your understanding with a short code puzzle—can you solve it?

You can also solve this puzzle and track your Python skills on our interactive Finxter app.

Syntax: You can call this method on each list object in Python. Here’s the syntax:

list.reverse()

Arguments: The reverse method doesn’t take any arguments.

Return value: The method list.reverse() has return value None. It reverses the elements of the list in place (but doesn’t create a new list). Thus, a return value is not needed.

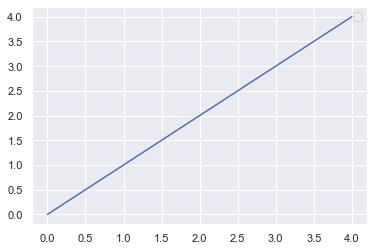

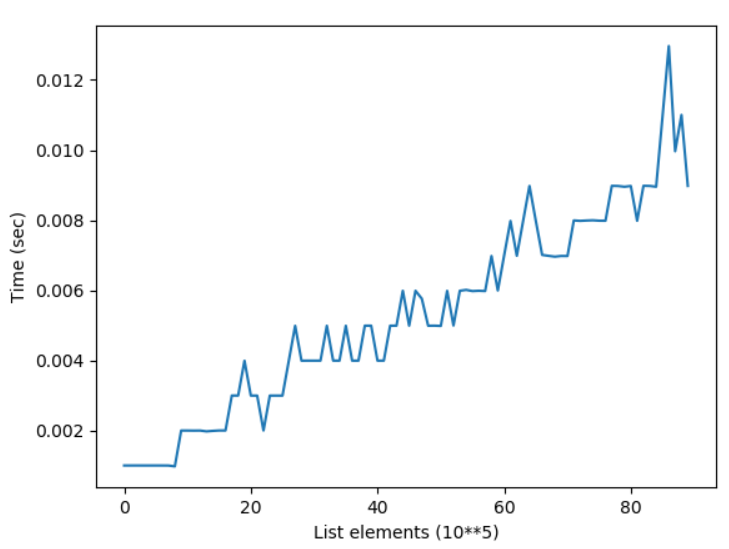

Python List reverse() Time Complexity

The time complexity of the reverse() operation is O(n) for a list with n elements. The standard Python implementation cPython “touches” all elements in the original list to move them to another position. Thus, the time complexity is linear in the number of list elements.

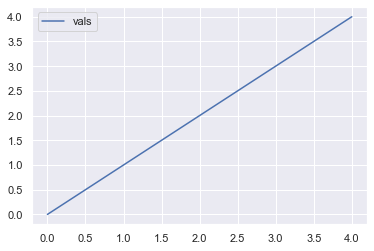

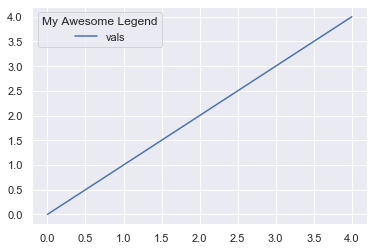

You can see a plot of the time complexity of the reverse() method for growing list size here:

The figure shows how the elapsed time of reversing lists with growing number of elements grows linear to the number of elements.

If you’re interested in the code I used to generate this plot with Matplotlib, this is it:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import time y = []

for i in [100000 * j for j in range(10,100)]: lst = list(range(i)) t0 = time.time() x = lst.reverse() t1 = time.time() y.append(t1-t0) plt.plot(y)

plt.xlabel("List elements (10**5)")

plt.ylabel("Time (sec)")

plt.show()

Python List reverse() In Place

If you call the list.reverse() method on any list object in Python, it reverses the list elements of this particular list object. You say that the reverse method happens in place.

This is a common mistake of many Python beginners. They assume that the reverse() method creates a new list with the elements in reversed order. This is not the case: the reverse() method modifies only the existing list object.

You can see this in the following example:

>>> lst = [1, 2, 3] >>> lst.reverse() >>> lst [3, 2, 1]

In the example, you only reversed the existing list lst. But you didn’t create a new list!

Python List reverse() None

The return value of the list.reverse() method is None. Why? Because the method reverses the list in place. This means that no new list is created. Instead, the method modifies the old list object.

You’ve seen an example of this in the previous section.

Python List Reverse List Without reverse()

You can also reverse a list without using the reverse() method. Let’s have a look at the following table that shows all reverse() alternatives:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

lst.reverse() |

Reverses the order of the elements of list lst in place. |

list(reversed(lst)) |

The built-in reversed(lst) method creates a new list object with reversed list elements. |

lst[::-1] |

Slicing with negative indexing is the most concise way of reversing the order of a list. It creates a new list object. |

[lst[i] for i in range(len(lst)-1,-1,-1)] |

Just for fun—one-liner solution to reverse a list using list comprehension and the negative range function. |

There is a fifth solution using recursion. But it’s highly inefficient and you shouldn’t use it in practice. If you want to learn about it anyways, read on. But don’t tell me you haven’t been warned!

Python List Reverse Recursive

You can create a recursive function to reverse any list. I’ll give you the code first and explain it later:

>>> reverse = lambda lst: reverse(lst[1:]) + [lst[0]] if lst else []

Let’s check if it does what it’s supposed to do (reversing the list):

>>> reverse([1, 2, 3]) [3, 2, 1] >>> reverse(["Ann", 1, 42, 0]) [0, 42, 1, 'Ann'] >>> reverse([]) [] >>> reverse([1]) [1]

Okay, it works!

The recursive one-liner solution uses several Python features you have to understand before you can understand it entirely:

- The lambda function

lambda x: ycreates an anonymous function with argumentxand return valuey. You can read the detailed tutorial on the Finxter blog. - List concatenation

[a, b, c] + [d]creates the new list[a, b, c, d]. You can read the detailed tutorial on the Finxter blog. - Slicing

lst[start:stop]carves out a subsequence from the list between thestartandstopindices. You can read the detailed tutorial on the Finxter blog. - The ternary operator

x if y else zreturns the valuexifyisTrue. In all other cases, it returns the valuez. You can read the detailed tutorial on the Finxter blog.

Phew! Quite some information to digest! But that’s not all. If you’ve understood all of the above, you also need to understand recursion. That’s too much to teach in a single paragraph so I’d send you over to my blog article about recursion.

I’ll say only that much: to understand recursion, you first need to understand recursion!

Python List Reverse Slice

Slicing is the easiest way to reverse a list.

To reverse the list lst, you simply use slicing operation lst[::-1] with default start and stop indices (not given) and negative step size -1 (given).

There’s only one case where you shouldn’t use slicing to reverse the list and this is if you don’t want to create a new list. In this case, stick to the lst.reverse() method which reverses the list in place.

Here’s an example of slicing to reverse a given list:

>>> friends = ["Ann", "Carsten", "Bob", "Alice"] >>> r_friends = friends[::-1] >>> friends ['Ann', 'Carsten', 'Bob', 'Alice'] >>> r_friends ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Carsten', 'Ann']

You see that the two lists friends and r_friends are independent objects in memory because the slicing operation creates a new list.

Related articles:

Python List Reverse Copy

There are two ways to copy a list and reverse the order of its elements:

- Use slicing

list[::-1], or - Call the

reversed(list)method and convert the result to a list using thelist(...)constructor.

Here are both in action:

>>> lst_1 = ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Ann'] >>> lst_2 = lst_1[::-1] >>> lst_3 = list(reversed(lst_1)) >>> lst_1 ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Ann'] >>> lst_2 ['Ann', 'Bob', 'Alice'] >>> lst_3 ['Ann', 'Bob', 'Alice']

Python List Partial Reverse

To partially reverse a list lst, use slicing with negative step size: lst[start:stop:-1]. The start and stop values define the part of the list to be reversed and the step size -1 means that you go through the list in reversed order.

Here’s an example of some partial list reversals:

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e'] >>> lst[5:2:-1] ['e', 'd'] >>> lst[:1:-1] ['e', 'd', 'c'] >>> lst[3:2:-1] ['d']

All of those slicing operations reversed a subsequence of the original list. Note that the start index must be larger or equal than the stop index because you traverse the list in negative order (well, if you don’t want to have an empty slice object).

Python List Reverse List Comprehension

You can reverse a list with Python’s powerful list comprehension method. (Although I cannot imagine a scenario where this would actually make sense.)

Related article:

List comprehension is a compact way of creating lists. The simple formula is [ expression + context ].

- Expression: What to do with each list element?

- Context: What list elements to select? It consists of an arbitrary number of for and if statements.

For example, the expression [x for x in range(3)] creates the list [0, 1, 2].

Here’s how you’d use list comprehension to reverse a list:

[lst[i] for i in range(len(lst)-1,-1,-1)]

You go over all indices in negative order—starting with the last list index len(lst)-1 and ending in the first list index 0. Note that the stop index is not included in the index sequence so I used the value -1 as the stop index for the range() built-in function.

Python List reverse() vs reversed()

What’s the difference between the method list.reverse() and the built-in function reversed(list)?

list.reverse()modifies an existing list in place and reverses the order of elements in this list object. No new list object is created.reversed(list)creates a new iterable object by reversing the order of elements of the originallist.

So you should use the former if you don’t want to create a new list and the latter if you want to create a new iterable without modifying the existing list.

An example is the following:

>>> lst_1 = [1, 2, 3] >>> lst_1.reverse() >>> lst_1 [3, 2, 1] >>> reversed(lst_1) <list_reverseiterator object at 0x0000025B58FEC9B0>

The output is not very intuitive but it only means that the reversed() function returns an iterable object.

Python List Deep Reverse

What if you want not only to reverse a list but running a deep reverse where all nested lists are also reversed in a recursive manner?

Here’s how you can do it:

def deep_reverse(lst): ''' Reverses a nested list in place''' # Reverse top-level list lst.reverse() # Recursively reverse all nested lists for element in lst: if isinstance(element, list): deep_reverse(element) lst = [1, 2, 3, [4, 5, 6]] deep_reverse(lst) print(lst)

This generates the output:

# OUTPUT: [[6, 5, 4], 3, 2, 1]

Not only the first-level list is reversed but also the second-level list. The code is loosely inspired from this article.

Python List Reverse Enumerate

The enumerate(list) built-in function returns a list of tuples with the first tuple value being the list index and the second tuple value being the list element.

You can reverse the order of enumerated tuples by stacking together the enumerate() function and the list.reverse() method as follows:

>>> for i, el in enumerate(list(reversed([1, 2, 3]))): print(i, el) 0 3 1 2 2 1

This way, you first reverse the list which creates an iterator. You then transform it into a list. The result can be enumerated.

If you want to reverse the order of the indices as well, simply switch the order of both functions:

>>> for i, el in reversed(list(enumerate([1, 2, 3]))): print(i, el) 2 3 1 2 0 1

By first enumerating, you calculate the indices based on the original list. Then you reverse them in the outer function.

Python List Reverse Iterator

The reversed(list) method returns an iterator, not a new list. This is different: an iterator is more efficient than a list. You can easily convert the iterator object into a list by using the list(...) built-in function.

Here’s an example:

>>> reversed([1, 2, 3]) <list_reverseiterator object at 0x0000021735E070B8> >>> for i in reversed([1, 2, 3]): print(i) 3 2 1

The iterator object doesn’t look pretty in the shell but it’s a more efficient way to iterate over a sequence of values than using lists. Why? Because lists need to maintain all values in memory. Iterators don’t.

Python List Reverse Sort

Do you want to sort a list in descending order? Use the reverse=True argument of the sorted() method. Here’s an example:

>>> sorted([42, 1, 99]) [1, 42, 99] >>> sorted([42, 1, 99], reverse=True) [99, 42, 1]

Python List reverse() Index

Rather than just using positive list indices, you can use reverse indexing in Python lists, too. The negative integer index -1 accesses the last element. The negative integer index -2 accesses the second last element and so on. Here’s an example:

>>> lst = ["Alice", "Bob", "Ann"] >>> lst[-1] 'Ann' >>> lst[-2] 'Bob' >>> lst[-3] 'Alice'

Python List Reverse range()

Do you want to iterate over a range of integer values in reverse order? Say, you want to iterate over the numbers from 10 to 0 in reverse order: 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0. You can simply achieve this by specifying the start, stop, and step arguments of the range(start, stop, step) method:

>>> for i in range(10, -1, -1): print(i) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

Note that the start argument is included in the range but the stop argument isn’t.

Python List reverse() Doesn’t Work

What if the reverse() method doesn’t work? Chances are that you assume the list.reverse() method has a return value—that is the reversed list. This is not the case! The list.reverse() method returns None because it reverses the list in place. It doesn’t return a new reversed list.

Here’s an example what you’re probably doing:

>>> lst = [1, 2, 3] >>> print(lst) [1, 2, 3] >>> print(lst.reverse()) None

If you really want to have a new list with elements in reversed order, use the Python built-in reversed(list) method:

>>> print(list(reversed([1, 2, 3]))) [3, 2, 1]

The reversed() method reverses the list and returns the reversed list as an iterator object. You need to convert it to a list first before printing it to the shell (and receiving a meaningful output).

Python Reverse List NumPy

To reverse a NumPy array (or even a Python list), you can simply use slicing with negative step size a[::-1]. Here’s an example:

>>> import numpy as np >>> a = np.array([1, 2, 3]) >>> a[::-1] array([3, 2, 1])

Python List reverse() Thread Safe

Do you have a multiple threads that access your list at the same time? Then you need to be sure that the list operations (such as reverse()) are actually thread safe.

In other words: can you call the reverse()

The answer is yes (if you use the cPython implementation). The reason is Python’s global interpreter lock that ensures that a thread that’s currently working on it’s code will first finish its current basic Python operation as defined by the cPython implementation. Only if it terminates with this operation will the next thread be able to access the computational resource. This is ensured with a sophisticated locking scheme by the cPython implementation.

The only thing you need to know is that each basic operation in the cPython implementation is atomic. It’s executed wholly and at once before any other thread has the chance to run on the same virtual engine. Therefore, there are no race conditions. An example for such a race condition would be the following: the first thread reads a value from the list, the second threads overwrites the value, and the first thread overwrites the value again invalidating the second thread’s operation.

All cPython operations are thread-safe. But if you combine those operations into higher-level functions, those are not generally thread safe as they consist of many (possibly interleaving) operations.

Where to Go From Here?

The list.reverse() method reverses the order of the list elements.

You’ve learned the ins and outs of this important Python list method.

If you keep struggling with those basic Python commands and you feel stuck in your learning progress, I’ve got something for you: Python One-Liners (Amazon Link).

In the book, I’ll give you a thorough overview of critical computer science topics such as machine learning, regular expression, data science, NumPy, and Python basics—all in a single line of Python code!

OFFICIAL BOOK DESCRIPTION: Python One-Liners will show readers how to perform useful tasks with one line of Python code. Following a brief Python refresher, the book covers essential advanced topics like slicing, list comprehension, broadcasting, lambda functions, algorithms, regular expressions, neural networks, logistic regression and more. Each of the 50 book sections introduces a problem to solve, walks the reader through the skills necessary to solve that problem, then provides a concise one-liner Python solution with a detailed explanation.