In previous installments (Fedora 32, Fedora 35), there was a strong focus on making things work with Docker on Fedora Linux. This article will focus on the final stage of this long journey. It will focus on migrating a cross-platform production set-up from Docker to Podman.

Background

Docker and Podman use the same open standard for containers. On top of this container standard, there are multiple ways of organizing containers together. Docker-Compose and Kubernetes are the two main technologies for this, although tools like Ansible are also popular.

On the business side though, there are strong differences. Docker is distributed with a non-free application called Docker Desktop, while Podman historically never had a UI. Docker started live in 2013 and had its rise to prominence in 2016. Podman started in 2018 and it has only become more popular in the last two years.

Podman was certainly not the first on the scene, and it has been fighting an uphill battle. Still, in many ways, this has been an opportunity. Podman can avoid some of the architectural errors that Docker made, and it can integrate with other tools that didn’t exist yet when Docker started.

Personal background

The previous articles about Docker and Fedora are based on the author’s professional life. At the company were I work, we heavily relied on Docker when I came on board. This meant that I needed Docker, and I started to document my struggles which ultimately lead to the first article. The second article was a follow-up to inform readers that most hurdles from the past were no longer a problem.

Podman Destkop

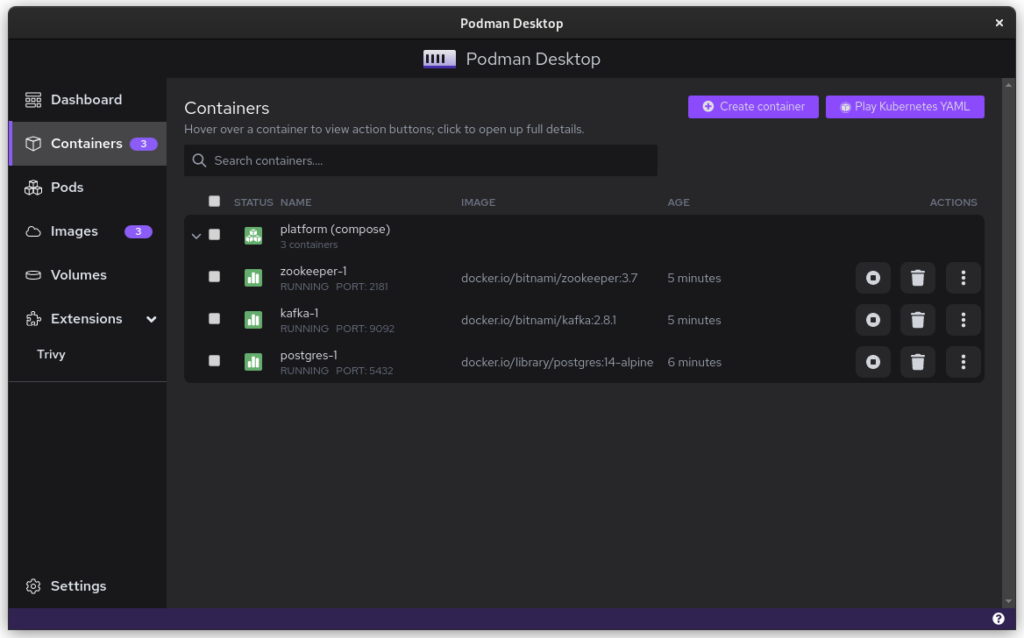

The game-changer in this whole story is Podman Desktop. It is a cross-platform UI that allows teams on Linux, macOS and Windows to collaborate. It works the same way as Docker Desktop, including a bundled VM and WSL support. This also means that Podman now offers a complete package for software companies. While software developers on Linux could use Podman in the past, it’s now possible to migrate an entire team across environments!

Migrating Docker

So, let’s start migrating from Docker to Podman. First, you’ll need to make sure that you have podman and podman-compose installed. You can easily download Podman Desktop from Flathub.

Image files

Image files are good as they are! They are identical because of the open standards behind containers.

One thing that you will see now is that there are a plethora of companies and groups that offer their own image-repositories.

- hub.docker.com (alias, docker.io) is the offering from Docker, which their tooling conveniently defaults to.

- registry.gitlab.com is the registry of GitLab’s commercial offering. Community editions follow this same syntax resulting in, for example: registry.gitlab.gnome.org

- registry.fedoraproject.org is Fedora’s Registry. This registry is also used for flatpaks from the Fedora repository.

- Quay.io is the offering from Red Hat, which contains all of Podman’s tooling, but also CentOS images.

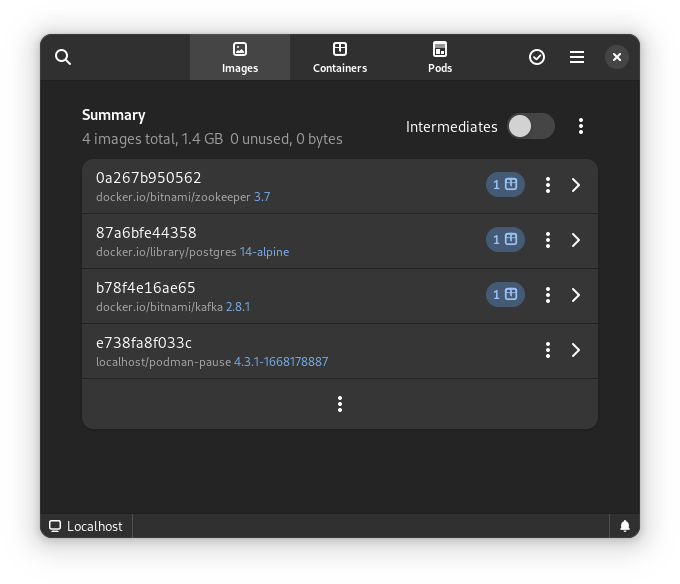

The biggest change that you’ll have to adapt to, when switching from Docker to Podman, is that you’ll be encouraged to write full image addresses instead of just stubs: `postgres:14-alpine` becomes `docker.io/library/postgres:14-alpine`.

Docker-Compose files

Compose files are Docker specific and they can’t be used with Podman. What you can use, though, is podman-compose. Better yet, you can start your docker-based platform and then use Podman Desktop to export your current configuration to a Kubernetes file.

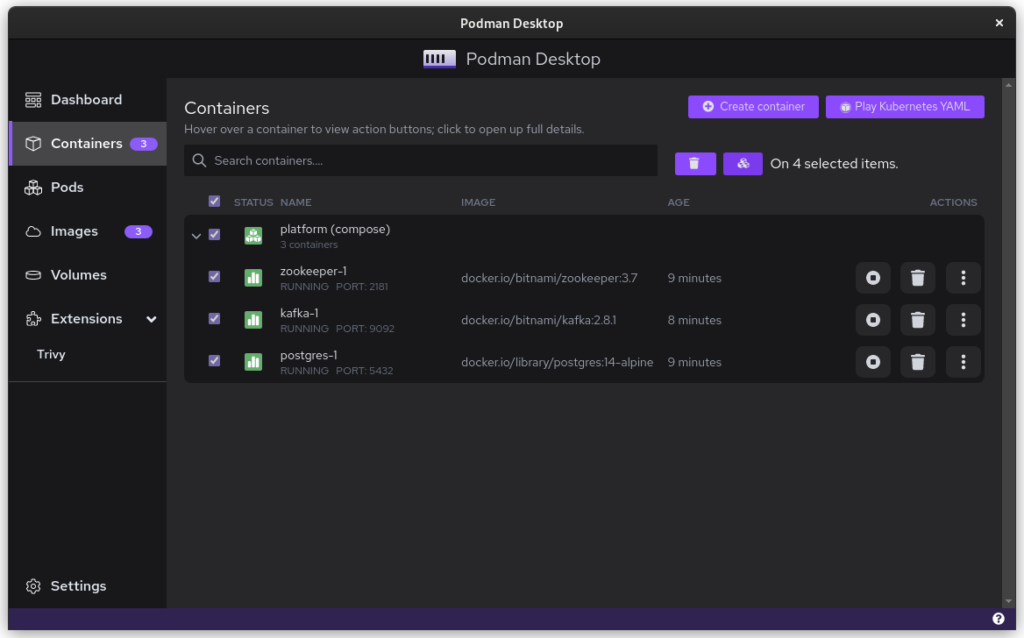

$ podman-compose -f ./docker-compose-platform.yaml up --detach

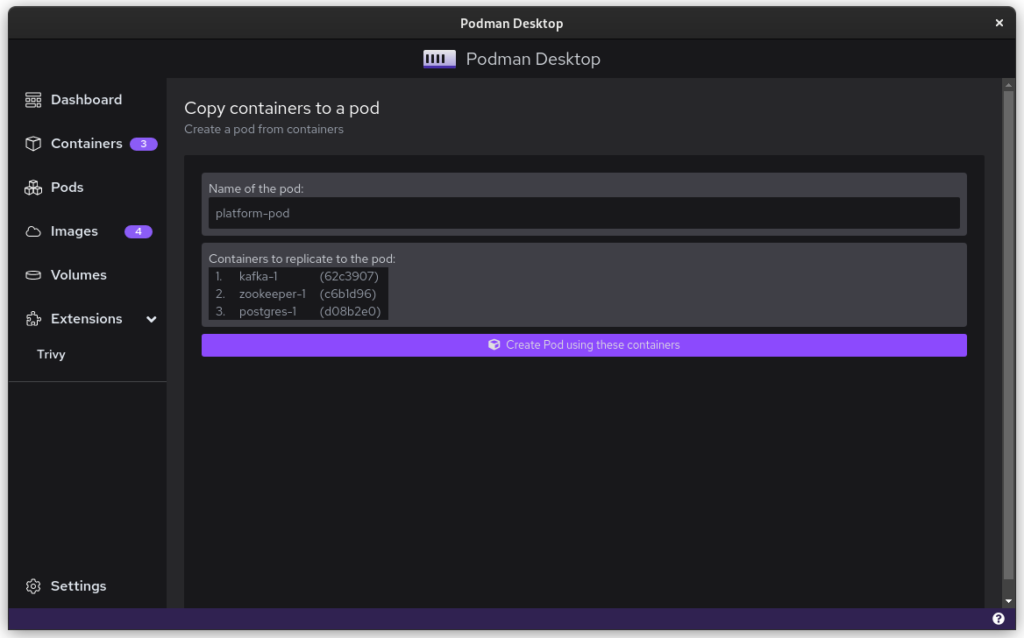

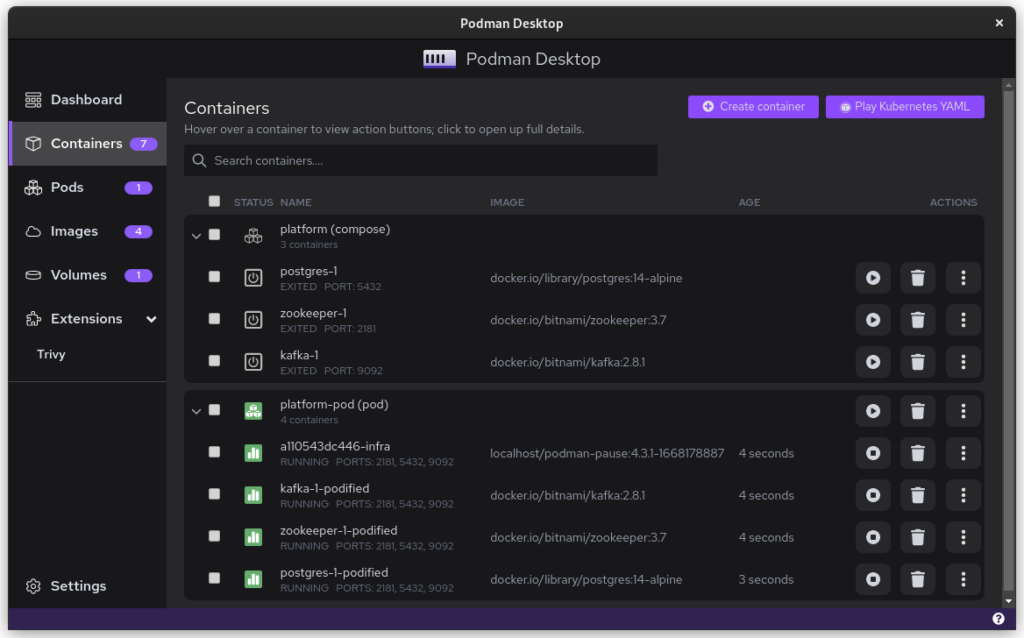

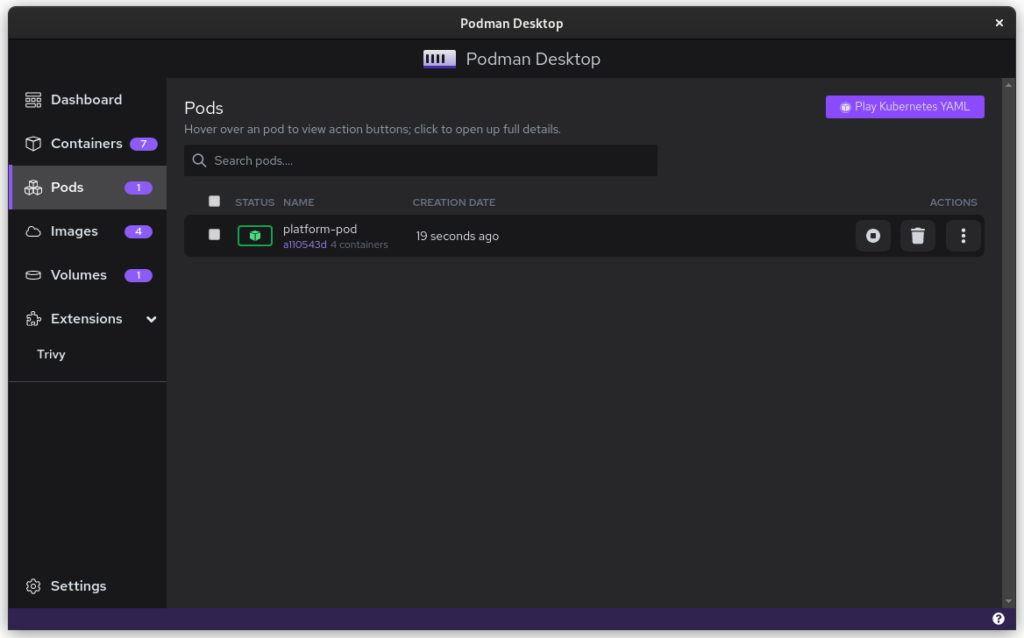

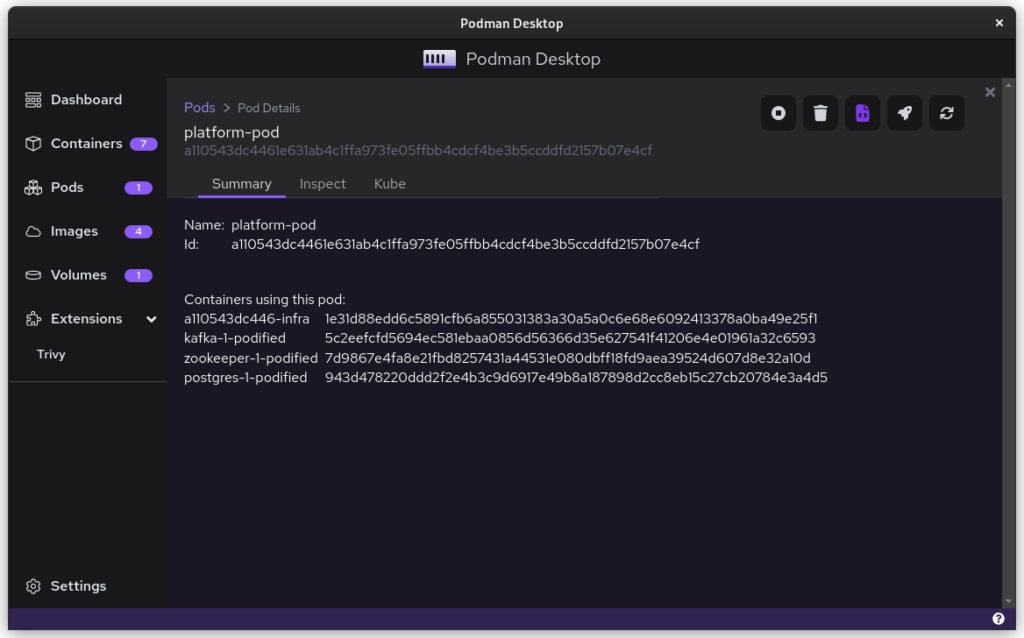

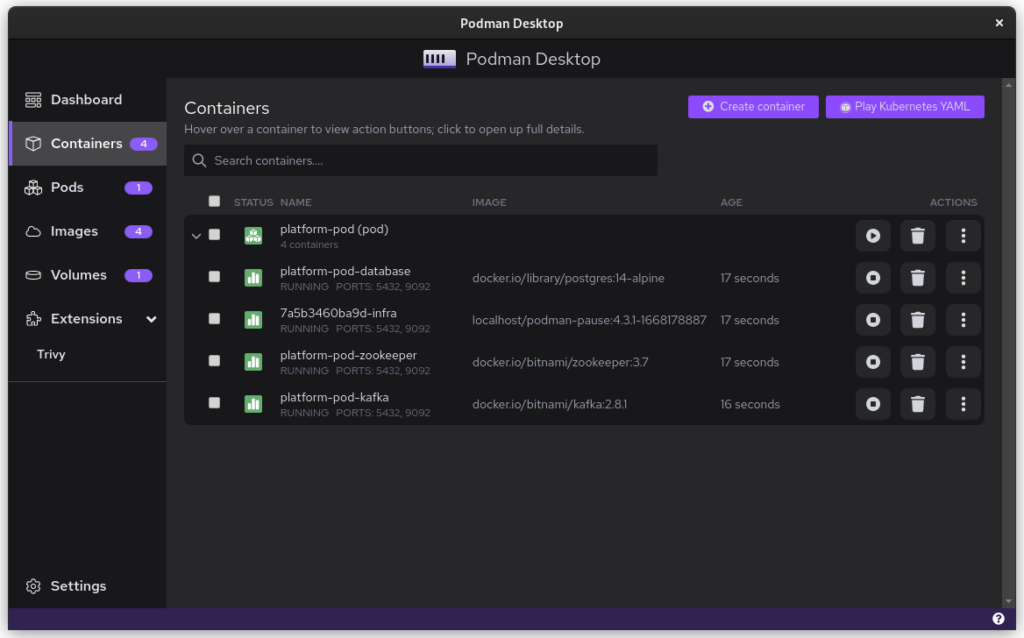

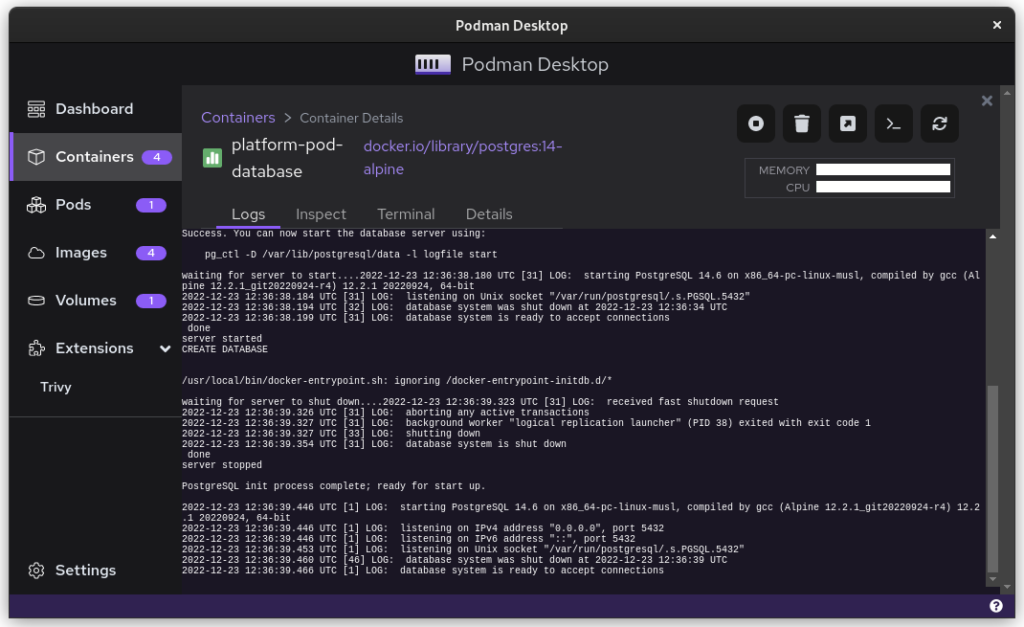

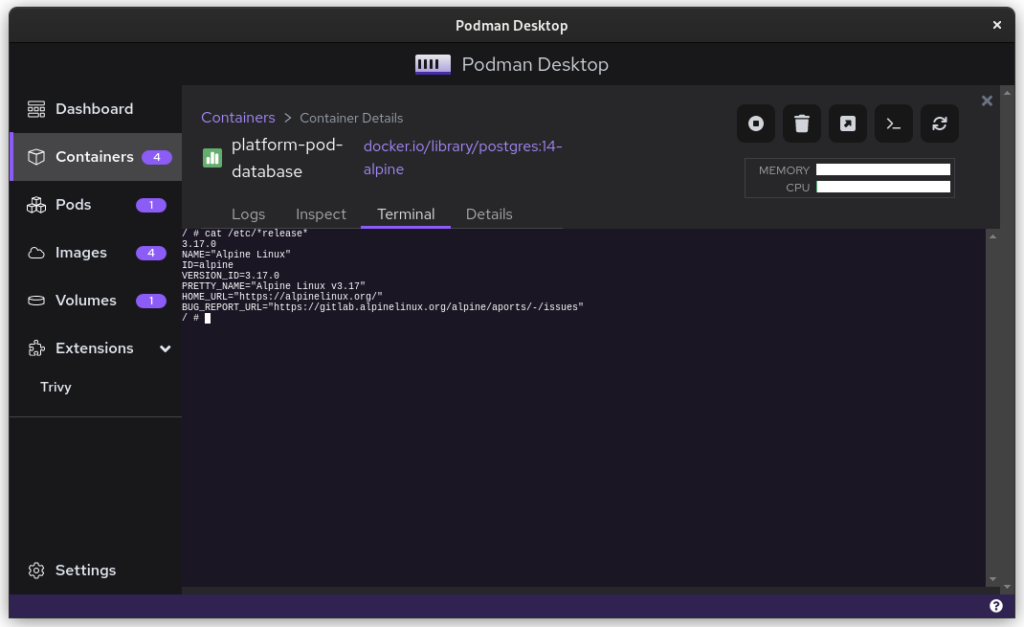

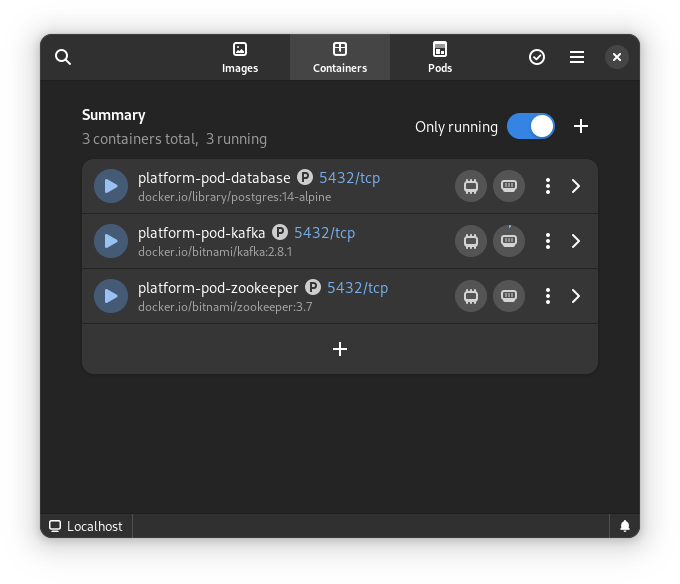

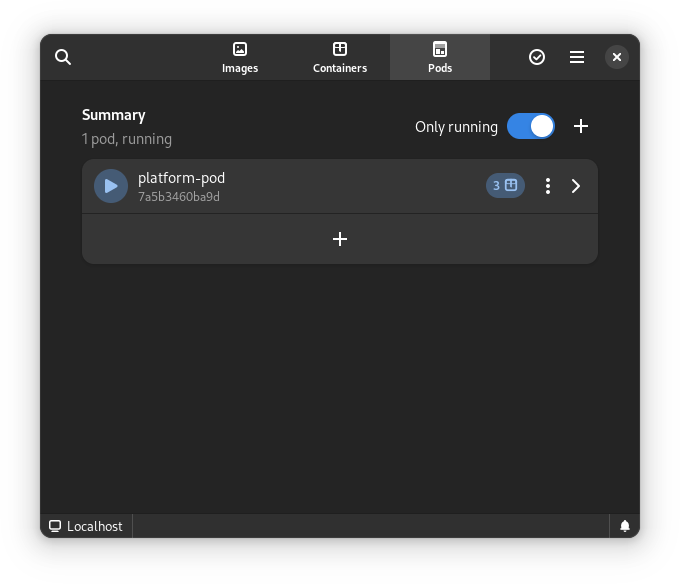

Once you start podman-compose with your old docker-compose .yaml file, you’ll see that you have a number of containers running in one ‘compose’ group. This is how things translate into the world of Podman. From here, you can select the containers and create a Pod. A Pod is a collection of containers that run in their own network.

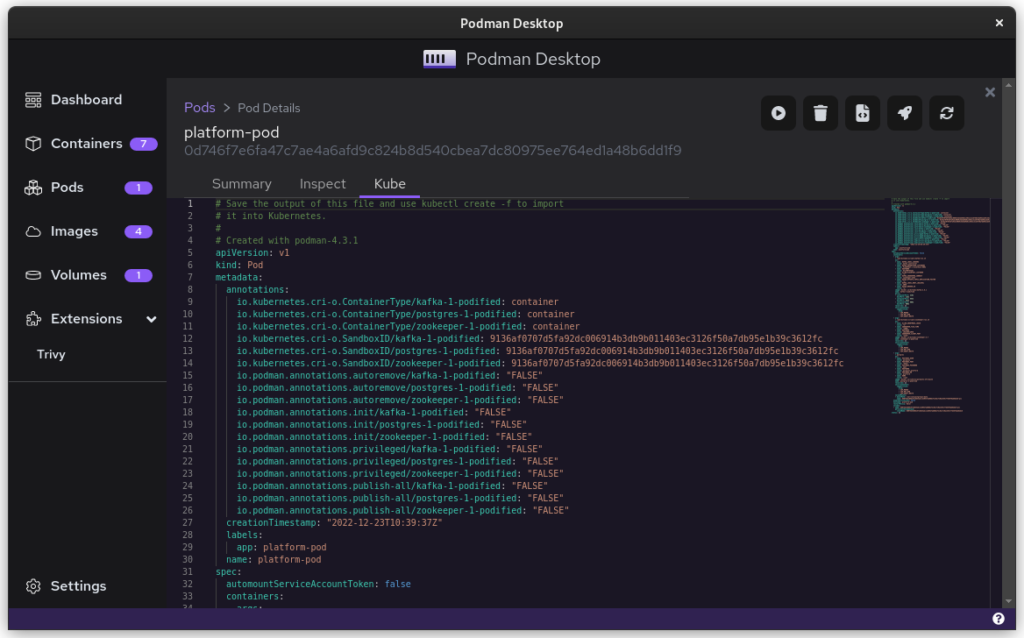

Once you inspect the Pod, you have a Kube file that represents this container collection. Save it somewhere and give it another critical look. You can likely remove some stuff without impacting the functioning of the system. After all, auto-generated documents will have some artifacts.

All three files from the demonstration can be seen here:

That’s it. You have now migrated from Docker to Podman. To start up Podman with the Kubernetes file simply do:

$ podman play kube podman-kube-platform-cleanup.yaml --replace

GitLab CI/CD

GitLab has a great set of open source and commercial offerings that allow you to automatically deploy and test your system. In the past, people working with Docker inside GitLab had to resort to a Docker-in-Docker solution. That gives many engineers headaches. A migration from Docker to Podman will resolve that problem.

For example, you can use Podman’s official image to easily build your own product image:

runner-setup: image: quay.io/podman/stable:latest stage: setup script: - podman login registry.gitlab.com -u ${COMPANY_CI_USERNAME} -p ${COMPANY_CI_PASSWORD} - podman build --pull --no-cache -t registry.gitlab.com/company/platform:latest -f ./distribute/image . - podman push registry.gitlab.com/company/platform:latest

In this example we use the official Podman stable image based on Fedora Linux 37. We use that to build the latest version of our platform based on the ./distribute/image file. We can do this all without ever having to set up Docker.

Tooling and integrations

Finally, we have to talk about certain tooling. Not all tooling will work equally well from the start. For example, the login that Amazon’s AWS CLI provides is hardcoded for Docker. Still, you can easily login to AWS by doing this:

$ aws ecr get-login-password --region $REGION | podman login --username AWS --password-stdin $AWS_REPO_NAME

Similarly, you can cache your registry credentials for both Podman and Docker. Do this with a single command like:

$ podman login registry.gitlab.com –authfile=${HOME}/.docker/config.json

Alternatives/Workarounds

Perhaps all of this sounds good, but you need more time to convince your team and company that embracing open source tools is great. In that case, you can add the following snippet to .bashrc and use Podman without changing the tooling of your team.

#Ensure that these aliases also affect other scripts shopt -s expand_aliases alias docker=podman alias docker-compose=podman-compose

This also offers you a chance to test the set-up that you have, in case of technical incompatibilities. You can also use the package podman-docker (available via dnf) to automatically convert Docker commands into Podman commands.

Company experience

The migration from Docker to Podman has been well received within my development team. The desktop experience for macOS and Windows users has improved since they no longer have to struggle with a tool that is closed source. The improvements to the CI system also help in maintaining the pipeline and it makes the integration tests run faster.

In day to day work, the team is really enthusiastic about the ease with which they can inspect running containers, manage images, and clean temporary volumes.

In the big picture, the migration from Docker to Podman further aids the company in limiting financial liabilities. Developers on macOS and Windows are no longer dependent on a closed-source product. Finally, it also means that the team gets some experience in Kubernetes, which will certainly pay off in the future.

Summary

The gains from switching to Podman really outweigh the bit of time it takes to set up and to migrate. The future is bright for Podman and Podman Desktop, and it offers a great solution to the problems that come with Docker.

Finally, for us Fedora Linux users, there is another great benefit. There is some beautiful tooling in development that can make our lives so much easier. The following screenshots are of the application Pods. This is currently in active development but will certainly prove to be a useful tool in the future.

This article has been made possible by my employer, Bold Security Technologies. Got your own migration stories to share? Let us know in the comments.