Quarkus is a framework for Java development that is described on their web site as:

A Kubernetes Native Java stack tailored for OpenJDK HotSpot and GraalVM, crafted from the best of breed Java libraries and standards

https://quarkus.io/ – Feb. 5, 2020

Silverblue — a Fedora Workstation variant with a container based workflow central to its functionality — should be an ideal host system for the Quarkus framework.

There are currently two ways to use Quarkus with Silverblue. It can be run in a pet container such as Toolbox/Coretoolbox. Or it can be run directly in a terminal emulator. This article will focus on the latter method.

Why Quarkus

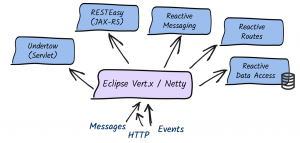

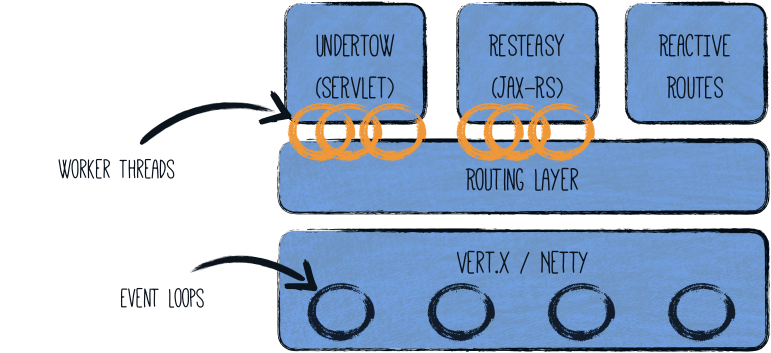

According to Quarkus.io: “Quarkus has been designed around a containers first philosophy. What this means in real terms is that Quarkus is optimized for low memory usage and fast startup times.” To achieve this, they employ first class support for Graal/Substrate VM, build time Metadata processing, reduction in reflection usage, and native image preboot. For details about why this matters, read Container First at Quarkus.

Prerequisites

A few prerequisites will need to configured before you can start using Quarkus. First, you need an IDE of your choice. Any of the popular ones will do. VIM or Emacs will work as well. The Quarkus site provides full details on how to set up the three major Java IDE’s (Eclipse, Intellij Idea, and Apache Netbeans). You will need a version of JDK installed. JDK 8, JDK 11 or any distribution of OpenJDK is fine. GrallVM 19.2.1 or 19.3.1 is needed for compiling down to native. You will also need Apache Maven 3.53+ or Gradle. This article will use Maven because that is what the author is more familiar with. Use the following command to layer Java 11 OpenJDK and Maven onto Silverblue:

$ rpm-ostree install java-11-openjdk* maven

Alternatively, you can download your favorite version of Java and install it directly in your home directory.

After rebooting, configure your JAVA_HOME and PATH environment variables to reference the new applications. Next, go to the GraalVM download page, and get GraalVM version 19.2.1 or version 19.3.1 for Java 11 OpenJDK. Install Graal as per the instructions provided. Basically, copy and decompress the archive into a directory under your home directory, then modify the PATH environment variable to include Graal. You use it as you would any JDK. So you can set it up as a platform in the IDE of your choice. Now is the time to setup the native image if you are going to use one. For more details on setting up your system to use Quarkus and the Quarkus native image, check out their Getting Started tutorial. With these parts installed and the environment setup, you can now try out Quarkus.

Bootstrapping

Quarkus recommends you create a project using the bootstrapping method. Below are some example commands entered into a terminal emulator in the Gnome shell on Silverblue.

$ mvn io.quarkus:quarkus-maven-plugin:1.2.1.Final:create \ -DprojectGroupId=org.jakfrost \ -DprojectArtifactId=silverblue-logo \ -DclassName="org.jakfrost.quickstart.GreetingResource" \ -Dpath="/hello" $ cd silverblue-logo

The bootstrapping process shown above will create a project under the current directory with the name silverblue-logo. After this completes, start the application in development mode:

$ ./mvnw compile quarkus:dev

With the application running, check whether it responds as expected by issuing the following command:

$ curl -w '\n' http://localhost:8080/hello

The above command should print hello on the next line. Alternatively, test the application by browsing to http://localhost:8080/hello with your web browser. You should see the same lonely hello on an otherwise empty page. Leave the application running for the next section.

Injection

Open the project in your favorite IDE. If you are using Netbeans, simply open the project directory where the pom.xml file resides. Now would be a good time to have a look at the pom.xml file.

Quarkus uses ArC for its dependency injection. ArC is a dependency of quarkus-resteasy, so it is already part of the core Quarkus installation. Add a companion bean to the project by creating a java class in your IDE called GreetingService.java. Then put the following code into it:

import javax.enterprise.context.ApplicationScoped; @ApplicationScoped

public class GreetingService { public String greeting(String name) { return "hello " + name; } }

The above code is a verbatim copy of what is used in the injection example in the Quarkus Getting Started tutorial. Modify GreetingResource.java by adding the following lines of code:

import javax.inject.Inject;

import org.jboss.resteasy.annotations.jaxrs.PathParam; @Inject GreetingService service;//inject the service @GET //add a getter to use the injected service @Produces(MediaType.TEXT_PLAIN) @Path("/greeting/{name}") public String greeting(@PathParam String name) { return service.greeting(name); }

If you haven’t stopped the application, it will be easy to see the effect of your changes. Just enter the following curl command:

$ curl -w '\n' http://localhost:8080/hello/greeting/Silverblue

The above command should print hello Silverblue on the following line. The URL should work similarly in a web browser. There are two important things to note:

- The application was running and Quarkus detected the file changes on the fly.

- The injection of code into the app was very easy to perform.

The native image

Next, package your application as a native image that will work in a podman container. Exit the application by pressing CTRL-C. Then use the following command to package it:

$ ./mvnw package -Pnative -Dquarkus.native.container-runtime=podman

Now, build the container:

$ podman build -f src/main/docker/Dockerfile.native -t silverblue-logo/silverblue-logo

Now run it with the following:

$ podman run -i --rm -p 8080:8080 localhost/silverblue-logo/silverblue-logo

To get the container build to successfully complete, it was necessary to copy the /target directory and contents into the src/main/docker/ directory. Investigation as to the reason why is still required, and though the solution used was quick and easy, it is not an acceptable way to solve the problem.

Now that you have the container running with the application inside, you can use the same methods as before to verify that it is working.

Point your browser to the URL http://localhost:8080/ and you should get a index.html that is automatically generated by Quarkus every time you create or modify an application. It resides in the src/main/resources/META-INF/resources/ directory. Drop other HTML files in this resources directory to have Quarkus serve them on request.

For example, create a file named logo.html in the resources directory containing the below markup:

<!DOCTYPE html> <!-- To change this license header, choose License Headers in Project Properties. To change this template file, choose Tools | Templates and open the template in the editor. --> <html> <head> <title>Silverblue</title> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0"> </head> <body> <div> <img src="fedora-silverblue-logo.png" alt="Fedora Silverblue"/> </div> </body> </html>

Next, save the below image alongside the logo.html file with the name fedora-silverblue-logo.png:

Now view the results at http://localhost:8080/logo.html.

Testing your application

Quarkus supports junit 5 tests. Look at your project’s pom.xml file. In it you should see two test dependencies. The generated project will contain a simple test, named GreetingResourceTest.java. Testing for the native file is only supported in prod mode. However, you can test the jar file in dev mode. These tests are RestAssured, but you can use whatever test library you wish with Quarkus. Use Maven to run the tests:

$ ./mvnw test

More details can be found in the Quarkus Getting Started tutorial.

Further reading and tutorials

Quarkus has an extensive collection of tutorials and guides. They are well worth the time to delve into the breadth of this microservices framework.

Quarkus also maintains a publications page that lists some very interesting articles on actual use cases of Quarkus. This article has only just scratched the surface of the topic. If what was presented here has piqued your interest, then follow the above links for more information.