What’s the best-kept productivity secret of code masters?

Here’s what ex-Google’s tech lead says is the most important skill as a coder (spoiler: it has to do with the topic of the tutorial):

Congratulations – you’re about to become a regular expression master. I’ve not only written the most comprehensive free regular expression tutorial on the web (16812 words) but also added a lot of tutorial videos wherever I saw fit.

So take your cup of coffee, scroll through the tutorial, and enjoy your brain cells getting active!

If you need to brush up your Python skills, feel free to read my Python Crash Course first.

Note that I use both both terms “regular expression” and the more concise “regex” in this tutorial.

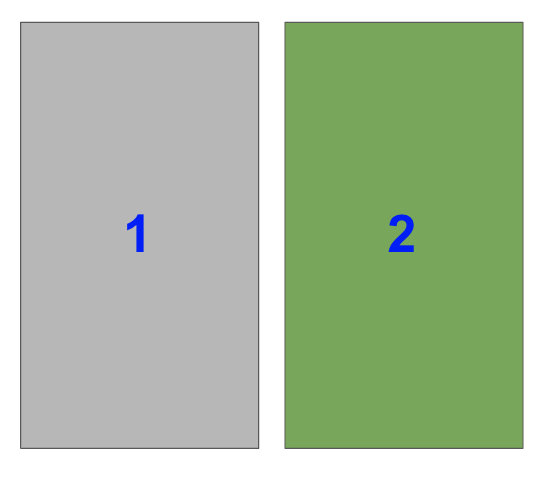

Regex Methods Overview

Python’s re module comes with a number of regular expression methods that help you achieve more with less.

Think of those methods as the framework connecting regular expressions with the Python programming language. Every programming language comes with its own way of handling regular expressions. For example, the Perl programming language has many built-in mechanisms for regular expressions—you don’t need to import a regular expression library—while the Java programming language provides regular expressions only within a library. This is also the approach of Python.

These are the most important regular expression methods of Python’s re module:

re.findall(pattern, string): Checks if the string matches the pattern and returns all occurrences of the matched pattern as a list of strings.re.search(pattern, string): Checks if the string matches the regex pattern and returns only the first match as a match object. The match object is just that: an object that stores meta information about the match such as the matching position and the matched substring.re.match(pattern, string): Checks if any string prefix matches the regex pattern and returns a match object.re.fullmatch(pattern, string): Checks if the whole string matches the regex pattern and returns a match object.re.compile(pattern): Creates a regular expression object from the pattern to speed up the matching if you want to use the regex pattern multiple times.re.split(pattern, string): Splits the string wherever the pattern regex matches and returns a list of strings. For example, you can split a string into a list of words by using whitespace characters as separators.re.sub(pattern, repl, string): Replaces (substitutes) the first occurrence of the regex pattern with the replacement string repl and return a new string.

Example: Let’s have a look at some examples of all the above functions:

import re text = '''

LADY CAPULET Alack the day, she's dead, she's dead, she's dead! CAPULET Ha! let me see her: out, alas! she's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. Nurse O lamentable day! ''' print(re.findall('she', text)) '''

Finds the pattern 'she' four times in the text: ['she', 'she', 'she', 'she'] ''' print(re.search('she', text)) '''

Finds the first match of 'she' in the text: <re.Match object; span=(34, 37), match='she'> The match object contains important information

such as the matched position. ''' print(re.match('she', text)) '''

Tries to match any string prefix -- but nothing found: None ''' print(re.fullmatch('she', text)) '''

Fails to match the whole string with the pattern 'she': None ''' print(re.split('\n', text)) '''

Splits the whole string on the new line delimiter '\n': ['', 'LADY CAPULET', '', " Alack the day, she's dead, she's dead, she's dead!", '', 'CAPULET', '', " Ha! let me see her: out, alas! she's cold:", ' Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff;', ' Life and these lips have long been separated:', ' Death lies on her like an untimely frost', ' Upon the sweetest flower of all the field.', '', 'Nurse', '', ' O lamentable day!', ''] ''' print(re.sub('she', 'he', text)) '''

Replaces all occurrences of 'she' with 'he': LADY CAPULET Alack the day, he's dead, he's dead, he's dead! CAPULET Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. Nurse O lamentable day! '''

Now, you know the most important regular expression functions. You know how to apply regular expressions to strings. But you don’t know how to write your regex patterns in the first place. Let’s dive into regular expressions and fix this once and for all!

Basic Regex Operations

A regular expression is a decades-old concept in computer science. Invented in the 1950s by famous mathematician Stephen Cole Kleene, the decades of evolution brought a huge variety of operations. Collecting all operations and writing up a comprehensive list would result in a very thick and unreadable book by itself.

Fortunately, you don’t have to learn all regular expressions before you can start using them in your practical code projects. Next, you’ll get a quick and dirty overview of the most important regex operations and how to use them in Python. In follow-up chapters, you’ll then study them in detail — with many practical applications and code puzzles.

Here are the most important regex operators:

.The wild-card operator (‘dot’) matches any character in a string except the newline character ‘\n’. For example, the regex ‘…’ matches all words with three characters such as ‘abc’, ‘cat’, and ‘dog’.*The zero-or-more asterisk operator matches an arbitrary number of occurrences (including zero occurrences) of the immediately preceding regex. For example, the regex ‘cat*’ matches the strings ‘ca’, ‘cat’, ‘catt’, ‘cattt’, and ‘catttttttt’.?The zero-or-one operator matches (as the name suggests) either zero or one occurrences of the immediately preceding regex. For example, the regex ‘cat?’ matches both strings ‘ca’ and ‘cat’ — but not ‘catt’, ‘cattt’, and ‘catttttttt’.+The at-least-one operator matches one or more occurrences of the immediately preceding regex. For example, the regex ‘cat+’ does not match the string ‘ca’ but matches all strings with at least one trailing character ‘t’ such as ‘cat’, ‘catt’, and ‘cattt’.^The start-of-string operator matches the beginning of a string. For example, the regex ‘^p’ would match the strings ‘python’ and ‘programming’ but not ‘lisp’ and ‘spying’ where the character ‘p’ does not occur at the start of the string.$The end-of-string operator matches the end of a string. For example, the regex ‘py$’ would match the strings ‘main.py’ and ‘pypy’ but not the strings ‘python’ and ‘pypi’.A|BThe OR operator matches either the regex A or the regex B. Note that the intuition is quite different from the standard interpretation of the or operator that can also satisfy both conditions. For example, the regex ‘(hello)|(hi)’ matches strings ‘hello world’ and ‘hi python’. It wouldn’t make sense to try to match both of them at the same time.ABThe AND operator matches first the regex A and second the regex B, in this sequence. We’ve already seen it trivially in the regex ‘ca’ that matches first regex ‘c’ and second regex ‘a’.

Note that I gave the above operators some more meaningful names (in bold) so that you can immediately grasp the purpose of each regex. For example, the ‘^’ operator is usually denoted as the ‘caret’ operator. Those names are not descriptive so I came up with more kindergarten-like words such as the “start-of-string” operator.

We’ve already seen many examples but let’s dive into even more!

import re text = ''' Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. ''' print(re.findall('.a!', text)) '''

Finds all occurrences of an arbitrary character that is

followed by the character sequence 'a!'.

['Ha!'] ''' print(re.findall('is.*and', text)) '''

Finds all occurrences of the word 'is',

followed by an arbitrary number of characters

and the word 'and'.

['is settled, and'] ''' print(re.findall('her:?', text)) '''

Finds all occurrences of the word 'her',

followed by zero or one occurrences of the colon ':'.

['her:', 'her', 'her'] ''' print(re.findall('her:+', text)) '''

Finds all occurrences of the word 'her',

followed by one or more occurrences of the colon ':'.

['her:'] ''' print(re.findall('^Ha.*', text)) '''

Finds all occurrences where the string starts with

the character sequence 'Ha', followed by an arbitrary

number of characters except for the new-line character. Can you figure out why Python doesn't find any?

[] ''' print(re.findall('\n$', text)) '''

Finds all occurrences where the new-line character '\n'

occurs at the end of the string.

['\n'] ''' print(re.findall('(Life|Death)', text)) '''

Finds all occurrences of either the word 'Life' or the

word 'Death'.

['Life', 'Death'] '''

In these examples, you’ve already seen the special symbol ‘\n’ which denotes the new-line character in Python (and most other languages). There are many special characters, specifically designed for regular expressions. Next, we’ll discover the most important special symbols.

Special Symbols

Regular expressions need special symbols like you need air to breathe. Some symbols such as the new line character ‘\n’ are vital for writing effective regular expressions in practice. Other symbols such as the word symbol ‘\w’ make your code more readable and concise being a one-symbol solution for the longer regex [a-zA-Z0-9_].

Many of those symbols are also available in other regex languages such as Perl. Thus, studying this list carefully will improve your conceptual strength in using regular expressions—independent from the concrete tool you use.

Let’s get a quick overview of the four most important special symbols in Python’s re library!

- \n The newline symbol is not a special symbol of the regex library, it’s a standard character. However, you’ll see the newline character so often that I just couldn’t write this list without including it. For example, the regex ‘hello\nworld’ matches a string where the string ‘hello’ is placed in one line and the string ‘world’ is placed into the second line.

- \t The tabular character is, like the newline character, not a special symbol of the regex library. It just encodes the tabular space ‘ ‘ which is different to a sequence of whitespaces ‘ ‘ (even if it doesn’t look different). For example, the regex ‘hello\n\tworld’ matches the string that consists of ‘hello’ in the first line and ‘ world’ in the second line (with a leading tab character).

- \s The whitespace character is, in contrast to the newline character, a special symbol of the regex libraries. You’ll find it in many other programming languages, too. The problem is that you often don’t know which type of whitespace is used: tabular characters, simple whitespaces, or even newlines. The whitespace character ‘\s’ simply matches any of them. For example, the regex ‘\s+hello\s+world’ would match the string ‘ \t \n hello \n \n \t world’, as well as ‘hello world’.

- \w The word character regex simplifies text processing significantly. If you want to match any word but you don’t want to write complicated subregexes to match a word character, you can simply use the word character regex \w to match any Unicode character. For example, the regex ‘\w+’ matches the strings ‘hello’, ‘bye’, ‘Python’, and ‘Python_is_great’.

- \W The negative word character. It matches any character that is not a word character.

- \b The word boundary regex is also a special symbol used in many regex tools. You can use it to match (as the name suggests) a word boundary between the \w and the \W character. But note that it matches only the empty string! You may ask: why does it exist if it doesn’t match any character? The reason is that it doesn’t “consume” the character right in front or right after a word. This way, you can search for whole words (or parts of words) and return only the word but not the delimiting character itself.

- \d The digit character matches all numeric symbols between 0 and 9. You can use it to match integers with an arbitrary number of digits: the regex ‘\d+’ matches integer numbers ‘10’, ‘1000’, ‘942’, and ‘99999999999’.

These are the most important special symbols and characters. A detailed examination follows in subsequent tutorials.

But before we move on, let’s understand them better by studying some examples!

import re text = ''' Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. ''' print(re.findall('\w+\W+\w+', text)) '''

Matches each pair of words in the text. ['Ha! let', 'me see', 'her: out', 'alas! he', 's cold', 'Her blood', 'is settled', 'and her', 'joints are', 'stiff;\n Life', 'and these', 'lips have', 'long been', 'separated:\n Death', 'lies on', 'her like', 'an untimely', 'frost\n Upon', 'the sweetest', 'flower of', 'all the'] Note that it matches also across new lines: 'stiff;\n Life'

is also matches! Note also that what is already matched is "consumed" and

doesn't match again. This is why the combination 'let me' is not

a matching substring. ''' print(re.findall('\d', text)) '''

No integers in the text: [ ] ''' print(re.findall('\n\t', text)) '''

Match all occurrences where a tab follows a newline: [ ] No match because each line starts with a sequence of four

whitespaces rather than the tab character. ''' print(re.findall('\n ', text)) '''

Match all occurrences where 4 whitespaces ' ' follow a newline: ['\n ', '\n ', '\n ', '\n ', '\n '] Matches all five lines. '''

Regex Methods

Yes, you’ve already studied the regex function superficially at the beginning of this tutorial. Now, you’re going to learn everything about those important functions in great detail.

findall()

The findall() method is the most basic way of using regular expressions in Python. So how does the re.findall() method work?

Let’s study its specification.

How Does the findall() Method Work in Python?

The re.findall(pattern, string) method finds all occurrences of the pattern in the string and returns a list of all matching substrings.

Specification:

re.findall(pattern, string, flags=0)

The re.findall() method has up to three arguments.

- pattern: the regular expression pattern that you want to match.

- string: the string which you want to search for the pattern.

- flags (optional argument): a more advanced modifier that allows you to customize the behavior of the function.

You’ll dive into each of them in a moment.

Return Value:

The re.findall() method returns a list of strings. Each string element is a matching substring of the string argument.

Let’s check out a few examples!

Examples re.findall()

First, you import the re module and create the text string to be searched for the regex patterns:

import re text = ''' Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. '''

Let’s say, you want to search the text for the string ‘her’:

>>> re.findall('her', text)

['her', 'her', 'her']

The first argument is the pattern you look for. In our case, it’s the string ‘her’. The second argument is the text to be analyzed. You stored the multi-line string in the variable text—so you take this as the second argument. You don’t need to define the optional third argument flags of the findall() method because you’re fine with the default behavior in this case.

Also note that the findall() function returns a list of all matching substrings. In this case, this may not be too useful because we only searched for an exact string. But if we search for more complicated patterns, this may actually be very useful:

>>> re.findall('\\bf\w+\\b', text)

['frost', 'flower', 'field']

The regex ‘\\bf\w+\\b’ matches all words that start with the character ‘f’.

You may ask: why to enclose the regex with a leading and trailing ‘\\b’? This is the word boundary character that matches the empty string at the beginning or at the end of a word. You can define a word as a sequence of characters that are not whitespace characters or other delimiters such as ‘.:,?!’.

In the previous example, you need to escape the boundary character ‘\b’ again because in a Python string, the default meaning of the character sequence ‘\b’ is the backslash character.

Summary

You now know that the re.findall(pattern, string) method matches all occurrences of the regex pattern in a given string—and returns a list of all matches as strings.

Intermezzo: Python Regex Flags

In many functions, you see a third argument flags. What are they and how do they work?

Flags allow you to control the regular expression engine. Because regular expressions are so powerful, they are a useful way of switching on and off certain features (e.g. whether to ignore capitalization when matching your regex).

For example, here’s how the third argument flags is used in the re.findall() method:

re.findall(pattern, string, flags=0)

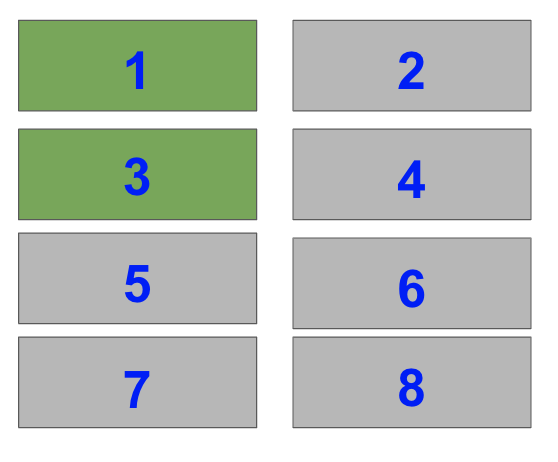

So the flags argument seems to be an integer argument with the default value of 0. To control the default regex behavior, you simply use one of the predefined integer values. You can access these predefined values via the re library:

| Syntax | Meaning |

| re.ASCII | If you don’t use this flag, the special Python regex symbols \w, \W, \b, \B, \d, \D, \s and \S will match Unicode characters. If you use this flag, those special symbols will match only ASCII characters — as the name suggests. |

| re.A | Same as re.ASCII |

| re.DEBUG | If you use this flag, Python will print some useful information to the shell that helps you debugging your regex. |

| re.IGNORECASE | If you use this flag, the regex engine will perform case-insensitive matching. So if you’re searching for [A-Z], it will also match [a-z]. |

| re.I | Same as re.IGNORECASE |

| re.LOCALE | Don’t use this flag — ever. It’s depreciated—the idea was to perform case-insensitive matching depending on your current locale. But it isn’t reliable. |

| re.L | Same as re.LOCALE |

| re.MULTILINE | This flag switches on the following feature: the start-of-the-string regex ‘^’ matches at the beginning of each line (rather than only at the beginning of the string). The same holds for the end-of-the-string regex ‘$’ that now matches also at the end of each line in a multi-line string. |

| re.M | Same as re.MULTILINE |

| re.DOTALL | Without using this flag, the dot regex ‘.’ matches all characters except the newline character ‘\n’. Switch on this flag to really match all characters including the newline character. |

| re.S | Same as re.DOTALL |

| re.VERBOSE | To improve the readability of complicated regular expressions, you may want to allow comments and (multi-line) formatting of the regex itself. This is possible with this flag: all whitespace characters and lines that start with the character ‘#’ are ignored in the regex. |

| re.X | Same as re.VERBOSE |

How to Use These Flags?

Simply include the flag as the optional flag argument as follows:

import re text = ''' Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. ''' print(re.findall('HER', text, flags=re.IGNORECASE))

# ['her', 'Her', 'her', 'her']

As you see, the re.IGNORECASE flag ensures that all occurrences of the string ‘her’ are matched—no matter their capitalization.

How to Use Multiple Flags?

Yes, simply add them together (sum them up) as follows:

import re text = ''' Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. ''' print(re.findall(' HER # Ignored', text, flags=re.IGNORECASE + re.VERBOSE))

# ['her', 'Her', 'her', 'her']

You use both flags re.IGNORECASE (all occurrences of lower- or uppercase string variants of ‘her’ are matched) and re.VERBOSE (ignore comments and whitespaces in the regex). You sum them together re.IGNORECASE + re.VERBOSE to indicate that you want to take both.

search()

This article is all about the search() method. To learn about the easy-to-use but less powerful findall() method that returns a list of string matches, check out our article about the similar findall() method.

So how does the re.search() method work? Let’s study the specification.

How Does re.search() Work in Python?

The re.search(pattern, string) method matches the first occurrence of the pattern in the string and returns a match object.

Specification:

re.search(pattern, string, flags=0)

The re.findall() method has up to three arguments.

- pattern: the regular expression pattern that you want to match.

- string: the string which you want to search for the pattern.

- flags (optional argument): a more advanced modifier that allows you to customize the behavior of the function. Want to know how to use those flags? Check out this detailed article on the Finxter blog.

We’ll explore them in more detail later.

Return Value:

The re.search() method returns a match object. You may ask (and rightly so):

What’s a Match Object?

If a regular expression matches a part of your string, there’s a lot of useful information that comes with it: what’s the exact position of the match? Which regex groups were matched—and where?

The match object is a simple wrapper for this information. Some regex methods of the re package in Python—such as search()—automatically create a match object upon the first pattern match.

At this point, you don’t need to explore the match object in detail. Just know that we can access the start and end positions of the match in the string by calling the methods m.start() and m.end() on the match object m:

>>> m = re.search('h...o', 'hello world')

>>> m.start()

0

>>> m.end()

5

>>> 'hello world'[m.start():m.end()] 'hello'

In the first line, you create a match object m by using the re.search() method. The pattern ‘h…o’ matches in the string ‘hello world’ at start position 0. You use the start and end position to access the substring that matches the pattern (using the popular Python technique of slicing).

Now, you know the purpose of the match() object in Python. Let’s check out a few examples of re.search()!

A Guided Example for re.search()

First, you import the re module and create the text string to be searched for the regex patterns:

>>> import re >>> text = ''' Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. '''

Let’s say you want to search the text for the string ‘her’:

>>> re.search('her', text)

<re.Match object; span=(20, 23), match='her'>

The first argument is the pattern to be found. In our case, it’s the string ‘her’. The second argument is the text to be analyzed. You stored the multi-line string in the variable text—so you take this as the second argument. You don’t need to define the optional third argument flags of the search() method because you’re fine with the default behavior in this case.

Look at the output: it’s a match object! The match object gives the span of the match—that is the start and stop indices of the match. We can also directly access those boundaries by using the start() and stop() methods of the match object:

>>> m = re.search('her', text)

>>> m.start()

20

>>> m.end()

23

The problem is that the search() method only retrieves the first occurrence of the pattern in the string. If you want to find all matches in the string, you may want to use the findall() method of the re library.

What’s the Difference Between re.search() and re.findall()?

There are two differences between the re.search(pattern, string) and re.findall(pattern, string) methods:

- re.search(pattern, string) returns a match object while re.findall(pattern, string) returns a list of matching strings.

- re.search(pattern, string) returns only the first match in the string while re.findall(pattern, string) returns all matches in the string.

Both can be seen in the following example:

>>> text = 'Python is superior to Python'

>>> re.search('Py...n', text)

<re.Match object; span=(0, 6), match='Python'>

>>> re.findall('Py...n', text)

['Python', 'Python']

The string ‘Python is superior to Python’ contains two occurrences of ‘Python’. The search() method only returns a match object of the first occurrence. The findall() method returns a list of all occurrences.

What’s the Difference Between re.search() and re.match()?

The methods re.search(pattern, string) and re.findall(pattern, string) both return a match object of the first match. However, re.match() attempts to match at the beginning of the string while re.search() matches anywhere in the string.

You can see this difference in the following code:

>>> text = 'Slim Shady is my name'

>>> re.search('Shady', text)

<re.Match object; span=(5, 10), match='Shady'>

>>> re.match('Shady', text)

>>>

The re.search() method retrieves the match of the ‘Shady’ substring as a match object. But if you use the re.match() method, there is no match and no return value because the substring ‘Shady’ does not occur at the beginning of the string ‘Slim Shady is my name’.

match()

The Python re.match() method is the third most-used regex method in Python. Let’s study the specification in detail.

How Does re.match() Work in Python?

The re.match(pattern, string) method matches the pattern at the beginning of the string and returns a match object.

Specification:

re.match(pattern, string, flags=0)

The re.match() method has up to three arguments.

- pattern: the regular expression pattern that you want to match.

- string: the string which you want to search for the pattern.

- flags (optional argument): a more advanced modifier that allows you to customize the behavior of the function.

We’ll explore them in more detail later.

Return Value:

The re.match() method returns a match object. You can access the start and end positions of the match in the string by calling the methods m.start() and m.end() on the match object m:

>>> m = re.match('h...o', 'hello world')

>>> m.start()

0

>>> m.end()

5

>>> 'hello world'[m.start():m.end()] 'hello'

In the first line, you create a match object m by using the re.match() method. The pattern ‘h…o’ matches in the string ‘hello world’ at start position 0. You use the start and end position to access the substring that matches the pattern (using the popular Python technique of slicing). But note that as the match() method always attempts to match only at the beginning of the string, the m.start() method will always return zero.

Now, you know the purpose of the match() object in Python. Let’s check out a few examples of re.match()!

A Guided Example for re.match()

First, you import the re module and create the text string to be searched for the regex patterns:

>>> import re >>> text = ''' Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. '''

Let’s say you want to search the text for the string ‘her’:

>>> re.match('lips', text)

>>>

The first argument is the pattern to be found: the string ‘lips’. The second argument is the text to be analyzed. You stored the multi-line string in the variable text—so you take this as the second argument. The third argument flags of the match() method is optional.

There’s no output! This means that the re.match() method did not return a match object. Why? Because at the beginning of the string, there’s no match for the regex pattern ‘lips’.

So how can we fix this? Simple, by matching all the characters that precede the string ‘lips’ in the text:

>>> re.match('(.|\n)*lips', text)

<re.Match object; span=(0, 122), match="\n Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold:\n>

The regex (.|\n)*lips matches all prefixes (an arbitrary number of characters including new lines) followed by the string ‘lips’. This results in a new match object that matches a huge substring from position 0 to position 122. Note that the match object doesn’t print the whole substring to the shell. If you access the matched substring, you’ll get the following result:

>>> m = re.match('(.|\n)*lips', text)

>>> text[m.start():m.end()] "\n Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold:\n Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff;\n Life and these lips"

Interestingly, you can also achieve the same thing by specifying the third flag argument as follows:

>>> m = re.match('.*lips', text, flags=re.DOTALL)

>>> text[m.start():m.end()] "\n Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold:\n Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff;\n Life and these lips"

The re.DOTALL flag ensures that the dot operator . matches all characters including the new line character.

What’s the Difference Between re.match() and re.findall()?

There are two differences between the re.match(pattern, string) and re.findall(pattern, string) methods:

- re.match(pattern, string) returns a match object while re.findall(pattern, string) returns a list of matching strings.

- re.match(pattern, string) returns only the first match in the string—and only at the beginning—while re.findall(pattern, string) returns all matches in the string.

Both can be seen in the following example:

>>> text = 'Python is superior to Python'

>>> re.match('Py...n', text)

<re.Match object; span=(0, 6), match='Python'>

>>> re.findall('Py...n', text)

['Python', 'Python']

The string ‘Python is superior to Python’ contains two occurrences of ‘Python’. The match() method only returns a match object of the first occurrence. The findall() method returns a list of all occurrences.

What’s the Difference Between re.match() and re.search()?

The methods re.search(pattern, string) and re.match(pattern, string) both return a match object of the first match. However, re.match() attempts to match at the beginning of the string while re.search() matches anywhere in the string.

You can see this difference in the following code:

>>> text = 'Slim Shady is my name'

>>> re.search('Shady', text)

<re.Match object; span=(5, 10), match='Shady'>

>>> re.match('Shady', text)

>>>

The re.search() method retrieves the match of the ‘Shady’ substring as a match object. But if you use the re.match() method, there is no match and no return value because the substring ‘Shady’ does not occur at the beginning of the string ‘Slim Shady is my name’.

fullmatch()

This section is all about the re.fullmatch(pattern, string) method of Python’s re library. There are two similar methods to help you use regular expressions:

- The findall(pattern, string) method returns a list of string matches. Check out our blog tutorial.

- The search(pattern, string) method returns a match object of the first match. Check out our blog tutorial.

- The match(pattern, string) method returns a match object if the regex matches at the beginning of the string. Check out our blog tutorial.

So how does the re.fullmatch() method work? Let’s study the specification.

How Does re.fullmatch() Work in Python?

The re.fullmatch(pattern, string) method returns a match object if the pattern matches the whole string.

Specification:

re.fullmatch(pattern, string, flags=0)

The re.fullmatch() method has up to three arguments.

- pattern: the regular expression pattern that you want to match.

- string: the string which you want to search for the pattern.

- flags (optional argument): a more advanced modifier that allows you to customize the behavior of the function. Want to know how to use those flags? Check out this detailed article on the Finxter blog.

We’ll explore them in more detail later.

Return Value:

The re.fullmatch() method returns a match object. You may ask (and rightly so): Let’s check out a few examples of re.fullmatch()!

A Guided Example for re.fullmatch()

First, you import the re module and create the text string to be searched for the regex patterns:

>>> import re >>> text = ''' Call me Ishmael. Some years ago--never mind how long precisely --having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. '''

Let’s say you want to match the full text with this regular expression:

>>> re.fullmatch('Call(.|\n)*', text)

>>>

The first argument is the pattern to be found: ‘Call(.|\n)*’. The second argument is the text to be analyzed. You stored the multi-line string in the variable text—so you take this as the second argument. The third argument flags of the fullmatch() method is optional and we skip it in the code.

There’s no output! This means that the re.fullmatch() method did not return a match object. Why? Because at the beginning of the string, there’s no match for the ‘Call’ part of the regex. The regex starts with an empty line!

So how can we fix this? Simple, by matching a new line character ‘\n’ at the beginning of the string.

>>> re.fullmatch('\nCall(.|\n)*', text)

<re.Match object; span=(0, 229), match='\nCall me Ishmael. Some years ago--never mind how>

The regex (.|\n)* matches an arbitrary number of characters (new line characters or not) after the prefix ‘\nCall’. This matches the whole text so the result is a match object. Note that there are 229 matching positions so the string included in resulting match object is only the prefix of the whole matching string. This fact is often overlooked by beginner coders.

What’s the Difference Between re.fullmatch() and re.match()?

The methods re.fullmatch(pattern, string) and re.match(pattern, string) both return a match object. Both attempt to match at the beginning of the string. The only difference is that re.fullmatch() also attempts to match the end of the string as well: it wants to match the whole string!

You can see this difference in the following code:

>>> text = 'More with less'

>>> re.match('More', text)

<re.Match object; span=(0, 4), match='More'>

>>> re.fullmatch('More', text)

>>>

The re.match(‘More’, text) method matches the string ‘More’ at the beginning of the string ‘More with less’. But the re.fullmatch(‘More’, text) method does not match the whole text. Therefore, it returns the None object—nothing is printed to your shell!

What’s the Difference Between re.fullmatch() and re.findall()?

There are two differences between the re.fullmatch(pattern, string) and re.findall(pattern, string) methods:

- re.fullmatch(pattern, string) returns a match object while re.findall(pattern, string) returns a list of matching strings.

- re.fullmatch(pattern, string) can only match the whole string, while re.findall(pattern, string) can return multiple matches in the string.

Both can be seen in the following example:

>>> text = 'the 42th truth is 42'

>>> re.fullmatch('.*?42', text)

<re.Match object; span=(0, 20), match='the 42th truth is 42'>

>>> re.findall('.*?42', text)

['the 42', 'th truth is 42']

Note that the regex .*? matches an arbitrary number of characters but it attempts to consume as few characters as possible. This is called “non-greedy” match (the *? operator). The fullmatch() method only returns a match object that matches the whole string. The findall() method returns a list of all occurrences. As the match is non-greedy, it finds two such matches.

What’s the Difference Between re.fullmatch() and re.search()?

The methods re.fullmatch() and re.search(pattern, string) both return a match object. However, re.fullmatch() attempts to match the whole string while re.search() matches anywhere in the string.

You can see this difference in the following code:

>>> text = 'Finxter is fun!'

>>> re.search('Finxter', text)

<re.Match object; span=(0, 7), match='Finxter'>

>>> re.fullmatch('Finxter', text)

>>>

The re.search() method retrieves the match of the ‘Finxter’ substring as a match object. But the re.fullmatch() method has no return value because the substring ‘Finxter’ does not match the whole string ‘Finxter is fun!’.

Summary

Now you know the re.fullmatch(pattern, string) method that attempts to match the whole string—and returns a match object if it succeeds or None if it doesn’t.

compile()

This article is all about the re.compile(pattern) method of Python’s re library. Before we dive into re.compile(), let’s get an overview of the four related methods you must understand:

- The findall(pattern, string) method returns a list of string matches.

- The search(pattern, string) method returns a match object of the first match. The match(pattern, string) method returns a match object if the regex matches at the beginning of the string.

- The fullmatch(pattern, string) method returns a match object if the regex matches the whole string.

Equipped with this quick overview of the most critical regex methods, let’s answer the following question:

How Does re.compile() Work in Python?

The re.compile(pattern) method returns a regular expression object (see next section)

You then use the object to call important regex methods such as search(string), match(string), fullmatch(string), and findall(string).

In short: You compile the pattern first. You search the pattern in a string second.

This two-step approach is more efficient than calling, say, search(pattern, string) at once. That is, IF you call the search() method multiple times on the same pattern. Why? Because you can reuse the compiled pattern multiple times.

Here’s an example:

import re # These two lines ...

regex = re.compile('Py...n')

match = regex.search('Python is great') # ... are equivalent to ...

match = re.search('Py...n', 'Python is great')

In both instances, the match variable contains the following match object:

<re.Match object; span=(0, 6), match='Python'>

But in the first case, we can find the pattern not only in the string ‘Python is great’ but also in other strings—without any redundant work of compiling the pattern again and again.

Specification:

re.compile(pattern, flags=0)

The method has up to two arguments.

- pattern: the regular expression pattern that you want to match.

- flags (optional argument): a more advanced modifier that allows you to customize the behavior of the function. Want to know how to use those flags? Check out this detailed article on the Finxter blog.

We’ll explore those arguments in more detail later.

Return Value:

The re.compile(patterns, flags) method returns a regular expression object. You may ask (and rightly so):

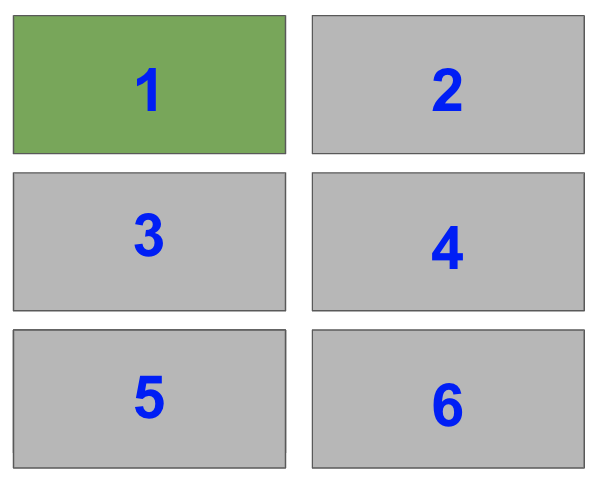

What’s a Regular Expression Object?

Python internally creates a regular expression object (from the Pattern class) to prepare the pattern matching process. You can call the following methods on the regex object:

| Method | Description |

| Pattern.search(string[, pos[, endpos]]) | Searches the regex anywhere in the string and returns a match object or None. You can define start and end positions of the search. |

| Pattern.match(string[, pos[, endpos]]) | Searches the regex at the beginning of the string and returns a match object or None. You can define start and end positions of the search. |

| Pattern.fullmatch(string[, pos[, endpos]]) | Matches the regex with the whole string and returns a match object or None. You can define start and end positions of the search. |

| Pattern.split(string, maxsplit=0) | Divides the string into a list of substrings. The regex is the delimiter. You can define a maximum number of splits. |

| Pattern.findall(string[, pos[, endpos]]) | Searches the regex anywhere in the string and returns a list of matching substrings. You can define start and end positions of the search. |

| Pattern.finditer(string[, pos[, endpos]]) | Returns an iterator that goes over all matches of the regex in the string (returns one match object after another). You can define the start and end positions of the search. |

| Pattern.sub(repl, string, count=0) | Returns a new string by replacing the first count occurrences of the regex in the string (from left to right) with the replacement string repl. |

| Pattern.subn(repl, string, count=0) | Returns a new string by replacing the first count occurrences of the regex in the string (from left to right) with the replacement string repl. However, it returns a tuple with the replaced string as the first and the number of successful replacements as the second tuple value. |

If you’re familiar with the most basic regex methods, you’ll realize that all of them appear in this table. But there’s one distinction: you don’t have to define the pattern as an argument. For example, the regex method re.search(pattern, string) will internally compile a regex object p and then call p.search(string).

You can see this fact in the official implementation of the re.search(pattern, string) method:

def search(pattern, string, flags=0): """Scan through string looking for a match to the pattern, returning a Match object, or None if no match was found.""" return _compile(pattern, flags).search(string)

(Source: GitHub repository of the re package)

The re.search(pattern, string) method is a mere wrapper for compiling the pattern first and calling the p.search(string) function on the compiled regex object p.

Is It Worth Using Python’s re.compile()?

No, in the vast majority of cases, it’s not worth the extra line.

Consider the following example:

import re # These two lines ...

regex = re.compile('Py...n')

match = regex.search('Python is great') # ... are equivalent to ...

match = re.search('Py...n', 'Python is great')

Don’t get me wrong. Compiling a pattern once and using it many times throughout your code (e.g., in a loop) comes with a big performance benefit. In some anecdotal cases, compiling the pattern first lead to 10x to 50x speedup compared to compiling it again and again.

But the reason it is not worth the extra line is that Python’s re library ships with an internal cache. At the time of this writing, the cache has a limit of up to 512 compiled regex objects. So for the first 512 times, you can be sure when calling re.search(pattern, string) that the cache contains the compiled pattern already.

Here’s the relevant code snippet from re’s GitHub repository:

# --------------------------------------------------------------------

# internals _cache = {} # ordered! _MAXCACHE = 512

def _compile(pattern, flags): # internal: compile pattern if isinstance(flags, RegexFlag): flags = flags.value try: return _cache[type(pattern), pattern, flags] except KeyError: pass if isinstance(pattern, Pattern): if flags: raise ValueError( "cannot process flags argument with a compiled pattern") return pattern if not sre_compile.isstring(pattern): raise TypeError("first argument must be string or compiled pattern") p = sre_compile.compile(pattern, flags) if not (flags & DEBUG): if len(_cache) >= _MAXCACHE: # Drop the oldest item try: del _cache[next(iter(_cache))] except (StopIteration, RuntimeError, KeyError): pass _cache[type(pattern), pattern, flags] = p return p

Can you find the spots where the cache is initialized and used?

While in most cases, you don’t need to compile a pattern, in some cases, you should. These follow directly from the previous implementation:

- You’ve got more than MAXCACHE patterns in your code.

- You’ve got more than MAXCACHE different patterns between two same pattern instances. Only in this case, you will see “cache misses” where the cache has already flushed the seemingly stale pattern instances to make room for newer ones.

- You reuse the pattern multiple times. Because if you don’t, it won’t make sense to use sparse memory to save them in your memory.

- (Even then, it may only be useful if the patterns are relatively complicated. Otherwise, you won’t see a lot of performance benefits in practice.)

To summarize, compiling the pattern first and storing the compiled pattern in a variable for later use is often nothing but “premature optimization”—one of the deadly sins of beginner and intermediate programmers.

What Does re.compile() Really Do?

It doesn’t seem like a lot, does it? My intuition was that the real work is in finding the pattern in the text—which happens after compilation. And, of course, matching the pattern is the hard part. But a sensible compilation helps a lot in preparing the pattern to be matched efficiently by the regex engine—work that would otherwise have be done by the regex engine.

Regex’s compile() method does a lot of things such as:

- Combine two subsequent characters in the regex if they together indicate a special symbol such as certain Greek symbols.

- Prepare the regex to ignore uppercase and lowercase.

- Check for certain (smaller) patterns in the regex.

- Analyze matching groups in the regex enclosed in parentheses.

The implemenation of the compile() method is not easy to read (trust me, I tried). It consists of many different steps.

Just note that all this work would have to be done by the regex engine at “matching runtime” if you wouldn’t compile the pattern first. If we can do it only once, it’s certainly a low-hanging fruit for performance optimizations—especially for long regular expression patterns.

How to Use the Optional Flag Argument?

As you’ve seen in the specification, the compile() method comes with an optional third ‘flag’ argument:

re.compile(pattern, flags=0)

Here’s how you’d use it in a practical example:

import re text = 'Python is great (python really is)' regex = re.compile('Py...n', flags=re.IGNORECASE) matches = regex.findall(text)

print(matches)

# ['Python', 'python']

Although your regex ‘Python’ is uppercase, we ignore the capitalization by using the flag re.IGNORECASE.

Summary

You’ve learned about the re.compile(pattern) method that prepares the regular expression pattern—and returns a regex object which you can use multiple times in your code.

split()

Why have regular expressions survived seven decades of technological disruption? Because coders who understand regular expressions have a massive advantage when working with textual data. They can write in a single line of code what takes others dozens!

This article is all about the re.split(pattern, string) method of Python’s re library.

Let’s answer the following question:

How Does re.split() Work in Python?

The re.split(pattern, string, maxsplit=0, flags=0) method returns a list of strings by matching all occurrences of the pattern in the string and dividing the string along those.

Here’s a minimal example:

>>> import re

>>> string = 'Learn Python with\t Finxter!'

>>> re.split('\s+', string)

['Learn', 'Python', 'with', 'Finxter!']

The string contains four words that are separated by whitespace characters (in particular: the empty space ‘ ‘ and the tabular character ‘\t’). You use the regular expression ‘\s+’ to match all occurrences of a positive number of subsequent whitespaces. The matched substrings serve as delimiters. The result is the string divided along those delimiters.

But that’s not all! Let’s have a look at the formal definition of the split method.

Specification

re.split(pattern, string, maxsplit=0, flags=0)

The method has four arguments—two of which are optional.

- pattern: the regular expression pattern you want to use as a delimiter.

- string: the text you want to break up into a list of strings.

- maxsplit (optional argument): the maximum number of split operations (= the size of the returned list). Per default, the maxsplit argument is 0, which means that it’s ignored.

- flags (optional argument): a more advanced modifier that allows you to customize the behavior of the function. Per default the regex module does not consider any flags. Want to know how to use those flags? Check out this detailed article on the Finxter blog.

The first and second arguments are required. The third and fourth arguments are optional.

You’ll learn about those arguments in more detail later.

Return Value:

The regex split method returns a list of substrings obtained by using the regex as a delimiter.

Regex Split Minimal Example

Let’s study some more examples—from simple to more complex.

The easiest use is with only two arguments: the delimiter regex and the string to be split.

>>> import re

>>> string = 'fgffffgfgPythonfgisfffawesomefgffg'

>>> re.split('[fg]+', string)

['', 'Python', 'is', 'awesome', '']

You use an arbitrary number of ‘f’ or ‘g’ characters as regular expression delimiters. How do you accomplish this? By combining the character class regex [A] and the one-or-more regex A+ into the following regex: [fg]+. The strings in between are added to the return list.

How to Use the maxsplit Argument?

What if you don’t want to split the whole string but only a limited number of times. Here’s an example:

>>> string = 'a-bird-in-the-hand-is-worth-two-in-the-bush'

>>> re.split('-', string, maxsplit=5)

['a', 'bird', 'in', 'the', 'hand', 'is-worth-two-in-the-bush']

>>> re.split('-', string, maxsplit=2)

['a', 'bird', 'in-the-hand-is-worth-two-in-the-bush']

We use the simple delimiter regex ‘-‘ to divide the string into substrings. In the first method call, we set maxsplit=5 to obtain six list elements. In the second method call, we set maxsplit=3 to obtain three list elements. Can you see the pattern?

You can also use positional arguments to save some characters:

>>> re.split('-', string, 2)

['a', 'bird', 'in-the-hand-is-worth-two-in-the-bush']

But as many coders don’t know about the maxsplit argument, you probably should use the keyword argument for readability.

How to Use the Optional Flag Argument?

As you’ve seen in the specification, the re.split() method comes with an optional fourth ‘flag’ argument:

re.split(pattern, string, maxsplit=0, flags=0)

Here’s how you’d use it in practice:

>>> import re

>>> re.split('[xy]+', text, flags=re.I)

['the', 'russians', 'are', 'coming']

Although your regex is lowercase, we ignore the capitalization by using the flag re.I which is short for re.IGNORECASE. If we wouldn’t do it, the result would be quite different:

>>> re.split('[xy]+', text)

['theXXXYYYrussiansXX', 'are', 'Y', 'coming']

As the character class [xy] only contains lowerspace characters ‘x’ and ‘y’, their uppercase variants appear in the returned list rather than being used as delimiters.

What’s the Difference Between re.split() and string.split() Methods in Python?

The method re.split() is much more powerful. The re.split(pattern, string) method can split a string along all occurrences of a matched pattern. The pattern can be arbitrarily complicated. This is in contrast to the string.split(delimiter) method which also splits a string into substrings along the delimiter. However, the delimiter must be a normal string.

An example where the more powerful re.split() method is superior is in splitting a text along any whitespace characters:

import re text = ''' Ha! let me see her: out, alas! he's cold: Her blood is settled, and her joints are stiff; Life and these lips have long been separated: Death lies on her like an untimely Frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field. ''' print(re.split('\s+', text)) '''

['', 'Ha!', 'let', 'me', 'see', 'her:', 'out,', 'alas!', "he's", 'cold:', 'Her', 'blood', 'is', 'settled,', 'and', 'her', 'joints', 'are', 'stiff;', 'Life', 'and', 'these', 'lips', 'have', 'long', 'been', 'separated:', 'Death', 'lies', 'on', 'her', 'like', 'an', 'untimely', 'Frost', 'Upon', 'the', 'sweetest', 'flower', 'of', 'all', 'the', 'field.', ''] '''

The re.split() method divides the string along any positive number of whitespace characters. You couldn’t achieve such a result with string.split(delimiter) because the delimiter must be a constant-sized string.

Summary

You’ve learned about the re.split(pattern, string) method that divides the string along the matched pattern occurrences and returns a list of substrings.

sub()

Do you want to replace all occurrences of a pattern in a string? You’re in the right place! This article is all about the re.sub(pattern, string) method of Python’s re library.

Let’s answer the following question:

How Does re.sub() Work in Python?

The re.sub(pattern, repl, string, count=0, flags=0) method returns a new string where all occurrences of the pattern in the old string are replaced by repl.

Here’s a minimal example:

>>> import re

>>> text = 'C++ is the best language. C++ rocks!'

>>> re.sub('C\+\+', 'Python', text) 'Python is the best language. Python rocks!'

>>>

The text contains two occurrences of the string ‘C++’. You use the re.sub() method to search all of those occurrences. Your goal is to replace all those with the new string ‘Python’ (Python is the best language after all).

Note that you must escape the ‘+’ symbol in ‘C++’ as otherwise it would mean the at-least-one regex.

You can also see that the sub() method replaces all matched patterns in the string—not only the first one.

But there’s more! Let’s have a look at the formal definition of the sub() method.

Specification

re.sub(pattern, repl, string, count=0, flags=0)

The method has four arguments—two of which are optional.

- pattern: the regular expression pattern to search for strings you want to replace.

- repl: the replacement string or function. If it’s a function, it needs to take one argument (the match object) which is passed for each occurrence of the pattern. The return value of the replacement function is a string that replaces the matching substring.

- string: the text you want to replace.

- count (optional argument): the maximum number of replacements you want to perform. Per default, you use count=0 which reads as replace all occurrences of the pattern.

- flags (optional argument): a more advanced modifier that allows you to customize the behavior of the method. Per default, you don’t use any flags.

The initial three arguments are required. The remaining two arguments are optional.

You’ll learn about those arguments in more detail later.

Return Value:

A new string where count occurrences of the first substrings that match the pattern are replaced with the string value defined in the repl argument.

Regex Sub Minimal Example

Let’s study some more examples—from simple to more complex.

The easiest use is with only three arguments: the pattern ‘sing’, the replacement string ‘program’, and the string you want to modify (text in our example).

>>> import re

>>> text = 'Learn to sing because singing is fun.'

>>> re.sub('sing', 'program', text) 'Learn to program because programing is fun.'

Just ignore the grammar mistake for now. You get the point: we don’t sing, we program.

But what if you want to actually fix this grammar mistake? After all, it’s programming, not programing. In this case, we need to substitute ‘sing’ with ‘program’ in some cases and ‘sing’ with ‘programm’ in other cases.

You see where this leads us: the sub argument must be a function! So let’s try this:

import re def sub(matched): if matched.group(0)=='singing': return 'programming' else: return 'program' text = 'Learn to sing because singing is fun.'

print(re.sub('sing(ing)?', sub, text))

# Learn to program because programming is fun.

In this example, you first define a substitution function sub. The function takes the matched object as an input and returns a string. If it matches the longer form ‘singing’, it returns ‘programming’. Else it matches the shorter form ‘sing’, so it returns the shorter replacement string ‘program’ instead.

How to Use the count Argument of the Regex Sub Method?

What if you don’t want to substitute all occurrences of a pattern but only a limited number of them? Just use the count argument! Here’s an example:

>>> import re

>>> s = 'xxxxxxhelloxxxxxworld!xxxx'

>>> re.sub('x+', '', s, count=2) 'helloworld!xxxx'

>>> re.sub('x+', '', s, count=3) 'helloworld!'

In the first substitution operation, you replace only two occurrences of the pattern ‘x+’. In the second, you replace all three.

You can also use positional arguments to save some characters:

>>> re.sub('x+', '', s, 3) 'helloworld!'

But as many coders don’t know about the count argument, you probably should use the keyword argument for readability.

How to Use the Optional Flag Argument?

As you’ve seen in the specification, the re.sub() method comes with an optional fourth flag argument:

re.sub(pattern, repl, string, count=0, flags=0)

What’s the purpose of the flags argument?

Flags allow you to control the regular expression engine. Because regular expressions are so powerful, they are a useful way of switching on and off certain features (for example, whether to ignore capitalization when matching your regex).

Here’s how you’d use the flags argument in a minimal example:

>>> import re

>>> s = 'xxxiiixxXxxxiiixXXX'

>>> re.sub('x+', '', s) 'iiiXiiiXXX'

>>> re.sub('x+', '', s, flags=re.I) 'iiiiii'

In the second substitution operation, you ignore the capitalization by using the flag re.I which is short for re.IGNORECASE. That’s why it substitutes even the uppercase ‘X’ characters that now match the regex ‘x+’, too.

What’s the Difference Between Regex Sub and String Replace?

In a way, the re.sub() method is the more powerful variant of the string.replace() method which is described in detail on this Finxter blog article.

Why? Because you can replace all occurrences of a regex pattern rather than only all occurrences of a string in another string.

So with re.sub() you can do everything you can do with string.replace() but some things more!

Here’s an example:

>>> 'Python is python is PYTHON'.replace('python', 'fun') 'Python is fun is PYTHON'

>>> re.sub('(Python)|(python)|(PYTHON)', 'fun', 'Python is python is PYTHON') 'fun is fun is fun'

The string.replace() method only replaces the lowercase word ‘python’ while the re.sub() method replaces all occurrences of uppercase or lowercase variants.

Note, you can accomplish the same thing even easier with the flags argument.

>>> re.sub('python', 'fun', 'Python is python is PYTHON', flags=re.I) 'fun is fun is fun'

How to Remove Regex Pattern in Python?

Nothing simpler than that. Just use the empty string as a replacement string:

>>> re.sub('p', '', 'Python is python is PYTHON', flags=re.I) 'ython is ython is YTHON'

You replace all occurrences of the pattern ‘p’ with the empty string ”. In other words, you remove all occurrences of ‘p’. As you use the flags=re.I argument, you ignore capitalization.

Summary

You’ve learned the re.sub(pattern, repl, string, count=0, flags=0) method returns a new string where all occurrences of the pattern in the old string are replaced by repl.

The Dot Operator .

You’re about to learn one of the most frequently used regex operators: the dot regex . in Python’s re library.

What’s the Dot Regex in Python’s Re Library?

The dot regex . matches all characters except the newline character. For example, the regular expression ‘…’ matches strings ‘hey’ and ‘tom’. But it does not match the string ‘yo\ntom’ which contains the newline character ‘\n’.

Let’s study some basic examples to help you gain a deeper understanding.

>>> import re

>>> >>> text = '''But then I saw no harm, and then I heard

Each syllable that breath made up between them.'''

>>> re.findall('B..', text)

['But']

>>> re.findall('heard.Each', text)

[]

>>> re.findall('heard\nEach', text)

['heard\nEach']

>>>

You first import Python’s re library for regular expression handling. Then, you create a multi-line text using the triple string quotes.

Let’s dive into the first example:

>>> re.findall('B..', text)

['But']

You use the re.findall(pattern, string) method that finds all occurrences of the pattern in the string and returns a list of all matching substrings.

The first argument is the regular expression pattern ‘B..’. The second argument is the string to be searched for the pattern. You want to find all patterns starting with the ‘B’ character, followed by two arbitrary characters except the newline character.

The findall() method finds only one such occurrence: the string ‘But’.

The second example shows that the dot operator does not match the newline character:

>>> re.findall('heard.Each', text)

[]

In this example, you’re looking at the simple pattern ‘heard.Each’. You want to find all occurrences of string ‘heard’ followed by an arbitrary non-whitespace character, followed by the string ‘Each’.

But such a pattern does not exist! Many coders intuitively read the dot regex as an arbitrary character. You must be aware that the correct definition of the dot regex is an arbitrary character except the newline. This is a source of many bugs in regular expressions.

The third example shows you how to explicitly match the newline character ‘\n’ instead:

>>> re.findall('heard\nEach', text)

['heard\nEach']

Now, the regex engine matches the substring.

Naturally, the following relevant question arises:

How to Match an Arbitrary Character (Including Newline)?

The dot regex . matches a single arbitrary character—except the newline character. But what if you do want to match the newline character, too? There are two main ways to accomplish this.

- Use the re.DOTALL flag.

- Use a character class [.\n].

Here’s the concrete example showing both cases:

>>> import re

>>> >>> s = '''hello

python'''

>>> re.findall('o.p', s)

[]

>>> re.findall('o.p', s, flags=re.DOTALL)

['o\np']

>>> re.findall('o[.\n]p', s)

['o\np']

You create a multi-line string. Then you try to find the regex pattern ‘o.p’ in the string. But there’s no match because the dot operator does not match the newline character per default. However, if you define the flag re.DOTALL, the newline character will also be a valid match.

An alternative is to use the slightly more complicated regex pattern [.\n]. The square brackets enclose a character class—a set of characters that are all a valid match. Think of a character class as an OR operation: exactly one character must match.

What If You Actually Want to Match a Dot?

If you use the character ‘.’ in a regular expression, Python assumes that it’s the dot operator you’re talking about. But what if you actually want to match a dot—for example to match the period at the end of a sentence?

Nothing simpler than that: escape the dot regex by using the backslash: ‘\.’. The backslash nullifies the meaning of the special symbol ‘.’ in the regex. The regex engine now knows that you’re actually looking for the dot character, not an arbitrary character except newline.

Here’s an example:

>>> import re

>>> text = 'Python. Is. Great. Period.'

>>> re.findall('\.', text)

['.', '.', '.', '.']

The findall() method returns all four periods in the sentence as matching substrings for the regex ‘\.’.

In this example, you’ll learn how you can combine it with other regular expressions:

>>> re.findall('\.\s', text)

['. ', '. ', '. ']

Now, you’re looking for a period character followed by an arbitrary whitespace. There are only three such matching substrings in the text.

In the next example, you learn how to combine this with a character class:

>>> re.findall('[st]\.', text)

['s.', 't.']

You want to find either character ‘s’ or character ‘t’ followed by the period character ‘.’. Two substrings match this regex.

Note that skipping the backslash is required. If you forget this, it can lead to strange behavior:

>>> re.findall('[st].', text)

['th', 's.', 't.']

As an arbitrary character is allowed after the character class, the substring ‘th’ also matches the regex.

Summary

You’ve learned everything you need to know about the dot regex . in this tutorial.

Summary: The dot regex . matches all characters except the newline character. For example, the regular expression ‘…’ matches strings ‘hey’ and ‘tom’. But it does not match the string ‘yo\ntom’ which contains the newline character ‘\n’.

The Asterisk Operator *

Every computer scientist knows the asterisk quantifier of regular expressions. But many non-techies know it, too. Each time you search for a text file *.txt on your computer, you use the asterisk operator.

This section is all about the asterisk * quantifier.

What’s the Python Re * Quantifier?

When applied to regular expression A, Python’s A* quantifier matches zero or more occurrences of A. The * quantifier is called asterisk operator and it always applies only to the preceding regular expression. For example, the regular expression ‘yes*’ matches strings ‘ye’, ‘yes’, and ‘yesssssss’. But it does not match the empty string because the asterisk quantifier * does not apply to the whole regex ‘yes’ but only to the preceding regex ‘s’.

Let’s study two basic examples to help you gain a deeper understanding. Do you get all of them?

>>> import re

>>> text = 'finxter for fast and fun python learning'

>>> re.findall('f.* ', text)

['finxter for fast and fun python ']

>>> re.findall('f.*? ', text)

['finxter ', 'for ', 'fast ', 'fun ']

>>> re.findall('f[a-z]*', text)

['finxter', 'for', 'fast', 'fun']

>>>

Don’t worry if you had problems understanding those examples. You’ll learn about them next. Here’s the first example:

Greedy Asterisk Example

>>> re.findall('f.* ', text)

['finxter for fast and fun python ']

The first argument of the re.findall() method is the regular expression pattern ‘f.* ‘. The second argument is the string to be searched for the pattern. In plain English, you want to find all patterns in the string that start with the character ‘f’, followed by an arbitrary number of optional characters, followed by an empty space.

The findall() method returns only one matching substring: ‘finxter for fast and fun python ‘. The asterisk quantifier * is greedy. This means that it tries to match as many occurrences of the preceding regex as possible. So in our case, it wants to match as many arbitrary characters as possible so that the pattern is still matched. Therefore, the regex engine “consumes” the whole sentence.

Non-Greedy Asterisk Example

But what if you want to find all words starting with an ‘f’? In other words: how to match the text with a non-greedy asterisk operator?

The second example is the following:

>>> re.findall('f.*? ', text)

['finxter ', 'for ', 'fast ', 'fun ']

In this example, you’re looking at a similar pattern with only one difference: you use the non-greedy asterisk operator *?. You want to find all occurrences of character ‘f’ followed by an arbitrary number of characters (but as few as possible), followed by an empty space.

Therefore, the regex engine finds four matches: the strings ‘finxter ‘, ‘for ‘, ‘fast ‘, and ‘fun ‘.

Asterisk + Character Class Example

The third example is the following:

>>> re.findall('f[a-z]*', text)

['finxter', 'for', 'fast', 'fun']

This regex achieves almost the same thing: finding all words starting with f. But you use the asterisk quantifier in combination with a character class that defines specifically which characters are valid matches.

Within the character class, you can define character ranges. For example, the character range [a-z] matches one lowercase character in the alphabet while the character range [A-Z] matches one uppercase character in the alphabet.

But note that the empty space is not part of the character class, so it won’t be matched if it appears in the text. Thus, the result is the same list of words that start with character f: ‘finxter ‘, ‘for ‘, ‘fast ‘, and ‘fun ‘.

What If You Want to Match the Asterisk Character Itself?

You know that the asterisk quantifier matches an arbitrary number of the preceding regular expression. But what if you search for the asterisk (or star) character itself? How can you search for it in a string?

The answer is simple: escape the asterisk character in your regular expression using the backslash. In particular, use ‘\*’ instead of ‘*’. Here’s an example:

>>> import re

>>> text = 'Python is ***great***'

>>> re.findall('\*', text)

['*', '*', '*', '*', '*', '*']

>>> re.findall('\**', text)

['', '', '', '', '', '', '', '', '', '', '***', '', '', '', '', '', '***', '']

>>> re.findall('\*+', text)

['***', '***']

You find all occurrences of the star symbol in the text by using the regex ‘\*’. Consequently, if you use the regex ‘\**’, you search for an arbitrary number of occurrences of the asterisk symbol (including zero occurrences). And if you would like to search for all maximal number of occurrences of subsequent asterisk symbols in a text, you’d use the regex ‘\*+’.

What’s the Difference Between Python Re * and ? Quantifiers?

You can read the Python Re A? quantifier as zero-or-one regex: the preceding regex A is matched either zero times or exactly once. But it’s not matched more often.

Analogously, you can read the Python Re A* operator as the zero-or-more regex (I know it sounds a bit clunky): the preceding regex A is matched an arbitrary number of times.

Here’s an example that shows the difference:

>>> import re

>>> re.findall('ab?', 'abbbbbbb')

['ab']

>>> re.findall('ab*', 'abbbbbbb')

['abbbbbbb']

The regex ‘ab?’ matches the character ‘a’ in the string, followed by character ‘b’ if it exists (which it does in the code).

The regex ‘ab*’ matches the character ‘a’ in the string, followed by as many characters ‘b’ as possible.

What’s the Difference Between Python Re * and + Quantifiers?

You can read the Python Re A* quantifier as zero-or-more regex: the preceding regex A is matched an arbitrary number of times.

Analogously, you can read the Python Re A+ operator as the at-least-once regex: the preceding regex A is matched an arbitrary number of times too—but at least once.

Here’s an example that shows the difference:

>>> import re

>>> re.findall('ab*', 'aaaaaaaa')

['a', 'a', 'a', 'a', 'a', 'a', 'a', 'a']

>>> re.findall('ab+', 'aaaaaaaa')

[]

The regex ‘ab*’ matches the character ‘a’ in the string, followed by an arbitary number of occurrences of character ‘b’. The substring ‘a’ perfectly matches this formulation. Therefore, you find that the regex matches eight times in the string.

The regex ‘ab+’ matches the character ‘a’, followed by as many characters ‘b’ as possible—but at least one. However, the character ‘b’ does not exist so there’s no match.

Summary: When applied to regular expression A, Python’s A* quantifier matches zero or more occurrences of A. The * quantifier is called asterisk operator and it always applies only to the preceding regular expression. For example, the regular expression ‘yes*’ matches strings ‘ye’, ‘yes’, and ‘yesssssss’. But it does not match the empty string because the asterisk quantifier * does not apply to the whole regex ‘yes’ but only to the preceding regex ‘s’.

The Zero-Or-One Operator: Question Mark (?)

Congratulations, you’re about to learn one of the most frequently used regex operators: the question mark quantifier A?.

What’s the Python Re ? Quantifier

When applied to regular expression A, Python’s A? quantifier matches either zero or one occurrences of A. The ? quantifier always applies only to the preceding regular expression. For example, the regular expression ‘hey?’ matches both strings ‘he’ and ‘hey’. But it does not match the empty string because the ? quantifier does not apply to the whole regex ‘hey’ but only to the preceding regex ‘y’.

Let’s study two basic examples to help you gain a deeper understanding. Do you get all of them?

>>> import re

>>>

>>> re.findall('aa[cde]?', 'aacde aa aadcde')

['aac', 'aa', 'aad']

>>>

>>> re.findall('aa?', 'accccacccac')

['a', 'a', 'a']

>>>

>>> re.findall('[cd]?[cde]?', 'ccc dd ee')

['cc', 'c', '', 'dd', '', 'e', 'e', '']

Don’t worry if you had problems understanding those examples. You’ll learn about them next. Here’s the first example:

>>> re.findall('aa[cde]?', 'aacde aa aadcde')

['aac', 'aa', 'aad']

You use the re.findall() method. Again, the re.findall(pattern, string) method finds all occurrences of the pattern in the string and returns a list of all matching substrings.

The first argument is the regular expression pattern ‘aa[cde]?’. The second argument is the string to be searched for the pattern. In plain English, you want to find all patterns that start with two ‘a’ characters, followed by one optional character—which can be either ‘c’, ‘d’, or ‘e’.

The findall() method returns three matching substrings:

- First, string ‘aac’ matches the pattern. After Python consumes the matched substring, the remaining substring is ‘de aa aadcde’.

- Second, string ‘aa’ matches the pattern. Python consumes it which leads to the remaining substring ‘ aadcde’.

- Third, string ‘aad’ matches the pattern in the remaining substring. What remains is ‘cde’ which doesn’t contain a matching substring anymore.

The second example is the following:

>>> re.findall('aa?', 'accccacccac')

['a', 'a', 'a']

In this example, you’re looking at the simple pattern ‘aa?’. You want to find all occurrences of character ‘a’ followed by an optional second ‘a’. But be aware that the optional second ‘a’ is not needed for the pattern to match.

Therefore, the regex engine finds three matches: the characters ‘a’.

The third example is the following:

>>> re.findall('[cd]?[cde]?', 'ccc dd ee')

['cc', 'c', '', 'dd', '', 'e', 'e', '']

This regex pattern looks complicated: ‘[cd]?[cde]?’. But is it really?

Let’s break it down step-by-step:

The first part of the regex [cd]? defines a character class [cd] which reads as “match either c or d”. The question mark quantifier indicates that you want to match either one or zero occurrences of this pattern.

The second part of the regex [cde]? defines a character class [cde] which reads as “match either c, d, or e”. Again, the question mark indicates the zero-or-one matching requirement.

As both parts are optional, the empty string matches the regex pattern. However, the Python regex engine attempts as much as possible.

Thus, the regex engine performs the following steps:

- The first match in the string ‘ccc dd ee’ is ‘cc’. The regex engine consumes the matched substring, so the string ‘c dd ee’ remains.

- The second match in the remaining string is the character ‘c’. The empty space ‘ ‘ does not match the regex so the second part of the regex [cde] does not match. Because of the question mark quantifier, this is okay for the regex engine. The remaining string is ‘ dd ee’.

- The third match is the empty string ”. Of course, Python does not attempt to match the same position twice. Thus, it moves on to process the remaining string ‘dd ee’.

- The fourth match is the string ‘dd’. The remaining string is ‘ ee’.

- The fifth match is the string ”. The remaining string is ‘ee’.

- The sixth match is the string ‘e’. The remaining string is ‘e’.

- The seventh match is the string ‘e’. The remaining string is ”.

- The eighth match is the string ”. Nothing remains.

This was the most complicated of our examples. Congratulations if you understood it completely!

What’s the Difference Between Python Re ? and * Quantifiers?

You can read the Python Re A? quantifier as zero-or-one regex: the preceding regex A is matched either zero times or exactly once. But it’s not matched more often.

Analogously, you can read the Python Re A* operator as the zero-or-multiple-times regex (I know it sounds a bit clunky): the preceding regex A is matched an arbitrary number of times.

Here’s an example that shows the difference:

>>> import re

>>> re.findall('ab?', 'abbbbbbb')

['ab']

>>> re.findall('ab*', 'abbbbbbb')

['abbbbbbb']

The regex ‘ab?’ matches the character ‘a’ in the string, followed by character ‘b’ if it exists (which it does in the code).

The regex ‘ab*’ matches the character ‘a’ in the string, followed by as many characters ‘b’ as possible.

What’s the Difference Between Python Re ? and + Quantifiers?